4A case for a racial justice agenda in treatment and research

By Kenyon Farrow

The Tuskegee Syphilis study remains a primary citation in both the scientific literature and popular conversations to explain the reluctance of African Americans to engage with the US healthcare system—from partaking in regular medical visits and preventive care, to adherence to medications (including antiretrovirals) to participation in clinical research trials for the development of new diagnostics, treatments, vaccines, or curative therapies.

Unfortunately, this places the onus of health disparities onto African Americans, and not on the systems responsible for both the legacy of mistrust of health care and biomedical research and the continued inequalities in access to care. The way forward is to begin reframing these disparities not simply as the consequences of conspiracy, but to actually create the contexts in which African Americans have access to influence and shape policy and programs through leadership development, community-education programs that demystify health care and biomedical research, and access to funding for community-organizing projects that challenge these systems to be more responsive to the needs of people of African descent in the US and abroad.

Unfortunately, this places the onus of health disparities onto African Americans, and not on the systems responsible for both the legacy of mistrust of health care and biomedical research and the continued inequalities in access to care. The way forward is to begin reframing these disparities not simply as the consequences of conspiracy, but to actually create the contexts in which African Americans have access to influence and shape policy and programs through leadership development, community-education programs that demystify health care and biomedical research, and access to funding for community-organizing projects that challenge these systems to be more responsive to the needs of people of African descent in the US and abroad.

When discussing HIV disparities, the Ebola outbreak of 2014 in West Africa, or other infectious diseases, it is not uncommon to hear African Americans refer to the Tuskegee Syphilis Study as proof of government conspiracies to either create or intentionally allow disease to spread within the community. Unfortunately, the facts of Tuskegee are deplorable and remain a reason for mistrust of biomedical research, medical care, and public health—distinctions that most people, not just African Americans, do not fully understand.

In 1932, the Public Health Service (PHS) and the Tuskegee Institute initiated the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male, in which 600 African American men in Macon County (399 men had syphilis, 201 did not) were enrolled to observe the natural progression of the disease. The men did not consent to being studied, and were told they were being treated for ‘bad blood’, a colloquial term poor rural African American communities used to describe illnesses that, without access to physicians or regular medical care, did not have a proper diagnosis. As studies were published, many people—particularly Black healthcare providers and researchers—criticized what was happening.

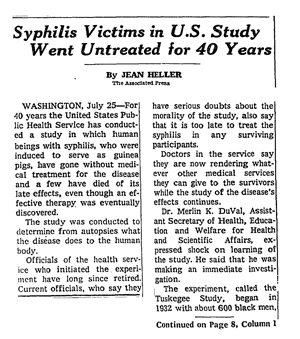

Not only was the lack of consent a great ethical violation, so was what happened next. In 1947, penicillin was standardized as the curative treatment for syphilis, yet the PHS researchers actively blocked the men from accessing care—including care provided by a rapid treatment center set up in Macon County. The study persisted until it was shut down following national controversy in 1972, and a series of national reforms to clinical research trials soon followed, as well as paid restitution to the surviving men and their families.

Nine years after the study was shut down, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report case reported five gay men suffering from a rare pneumonia, which ushered in the AIDS pandemic. Given the recency of the syphilis study in its chronological proximity to the discovery of HIV, is it any wonder there were—and remain—entrenched conspiracy theories in Black communities, or that African Americans remained skeptical of biomedical research, modern medical practice, and public health?

Recent studies of Black communities’ attitudes regarding HIV show that these rumors and conspiracies have continued to persist, and yet few, if any, public health approaches have been funded to directly engage communities in these myths and to provide educational resources to challenge the misperceptions, much less organize to address some of the persisting racial disparities that exist in biomedical research and access to treatment and care.

Government public health approaches have instead focused on knowledge and education about HIV risk factors for African Americans and the data illustrating the infection’s disproportionate impact. However, providing this information may actually be fueling mistrust, as opposed to undermining it. In February 2016, the CDC released data indicating that, if current trends continue, one in two Black men who have sex with men will contract HIV in their lifetime. Many Black gay activists were angry with the CDC for publishing these data without any thought or consideration to the persistent high levels of stigma and defeat. In my own conversations with Black gay activists since these statistics were released, I’ve learned many simply don’t believe the data anymore.

If the people in the community who have been invested in providing services or mobilizing Black gay men around the crisis have begun to tune out the CDC, what does that say for people in the community with far less access to information—who are already more likely to distrust public health, medical treatments, and research? A RAND Corporation telephone survey with a random sample of 500 African Americans published in the Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes in 2005 found that adult male participants who believed in conspiracy theories were less likely to use condoms. I recently had a discussion with a Black HIV-positive transgender woman and an advocate regarding her belief that there is a cure that is being intentionally withheld. Mistrust of government, health care and the pharmaceutical industry also made her skeptical of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP); she doesn’t encourage those who are HIV negative to explore taking it.

If the people in the community who have been invested in providing services or mobilizing Black gay men around the crisis have begun to tune out the CDC, what does that say for people in the community with far less access to information—who are already more likely to distrust public health, medical treatments, and research? A RAND Corporation telephone survey with a random sample of 500 African Americans published in the Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes in 2005 found that adult male participants who believed in conspiracy theories were less likely to use condoms. I recently had a discussion with a Black HIV-positive transgender woman and an advocate regarding her belief that there is a cure that is being intentionally withheld. Mistrust of government, health care and the pharmaceutical industry also made her skeptical of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP); she doesn’t encourage those who are HIV negative to explore taking it.

Although the hurdles seem high when it comes to shifting these dynamics, they are not insurmountable. A 2015 Kaiser Family Foundation survey assessing public attitudes and knowledge about HIV among Georgia residents found that, compared with white respondents, Black survey participants were far more likely to think HIV was a serious problem in the state, that people with HIV were regularly discriminated against, and were more likely to want more information to be available about HIV prevention, treatment, and how to support loved ones living with HIV. This suggests that, despite histories of real violations by public health and biomedical research, African Americans still crave access to basic information, and it’s clear that diffusing knowledge of treatment as prevention, the importance of viral suppression, and PrEP within Black communities has not been a public health priority. The work that many HIV activists are embarking on to effectively end the epidemic in the US—which includes ending racial disparities in transmission rates, morbidity, and mortality—must include a strategy to address the generations of medical and public healthcare mistrust among African Americans with the following actions:

- Demystify Research, Health Care, and Public Health. One of the reasons misinformation continues to persist is the scarcity of education efforts working to demystify biomedical research—even the basics of HIV and the science of transmission, treatment, prevention, and the current state of vaccine and cure development. Curricula and workshops, social media strategies, and traditional media outreach to engage African Americans on these issues are greatly underfunded, underdeveloped, and desperately needed. And that work has to be led by indigenous Black leadership.

- Reframe Treatment and Research. As activists, we have to do more to interrupt misinformation, not by strictly dismissing conspiracy theories, but by actually pointing to where there is institutional racism that has shaped disparities in HIV acquisition and access to prevention and care. Similar to Tuskegee, the existence of treatments that extend life and prevent infection being out of reach for most African Americans exemplifies institutional racism, and that’s what we should be fighting, as opposed to denying the benefits of these advances. Similarly, we must to make the pricing of various treatments—particularly PrEP, antiretroviral treatment, and Hepatitis C virus drugs—an issue of racial justice.

- Funding for Black Health/Medical Community Organizing and Advocacy Movement. With the exception of HIV community-based organizations (including harm reduction) and Black women’s groups largely focused on reproductive justice, there is very little infrastructure in place for Black activism on health and medical issues of any kind. This is contrary to the fact that African Americans have a long history of activism and advocacy for social justice in research, health care access, and treatment for a range of conditions including tuberculosis and sickle cell anemia, and African American civil rights groups (e.g., the National Medical Association, Congress of Racial Equality, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) were the leading advocates for the establishment of Medicare. We are going to need to provide leadership development and training—and perhaps even new national, state, and local organizations—to develop an infrastructure for Black leadership to use grassroots organizing, education, leadership development, policy advocacy, media, and direct action tactics to address health and medical issues from a racial justice perspective.

There are already dozens of community advisory boards that exist as part of organizations, federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), and centers for AIDS research (CFARs) that could be restructured to address broader social justice issues in health and medical care locally, make visible treatment and research activists as they currently exist in Black communities, and foster movement-building across other social justice organizations in the Black community, and in other communities as well.

I don’t know a Black HIV or healthcare activist that doesn’t face these questions about government or research conspiracies on a regular basis. Whether with an Uber driver, a barber, or a family member, as soon as people find out what you do, these kinds of questions and concerns emerge. But these issues could better be addressed if a social movement of Black healthcare and research activists could be better supported to both better engage community concerns that might improve healthcare engagement and to directly challenge the institutions, laws, and policies that actually do continue to perpetuate, as Black medical writer and historian Harriet Washington has described, medical apartheid.•

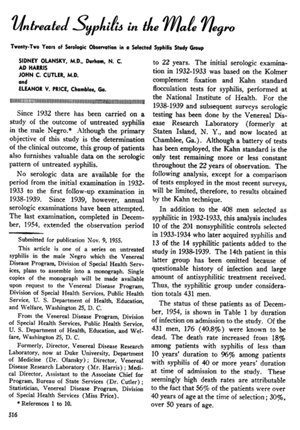

Image 1: Olansky S, Harris A, Cutler JC, Price EV. Untreated syphilis in the male negro: twenty-two years of serologic observation in a selected syphilis study group. AMA Arch Derm. 1956;73(5):516-522. doi:10.1001/archderm.1956.01550050094017.

Image 2: Heller J. “Syphilis victims in U.S. study went untreated for 40 years.” The New York Times. 1972 July 26.