Preparing to defend and reshape a still-critical program

By Coco Jervis

An increasing demand for services, coupled with significant fiscal retrenchment among federal and state agencies, leaves the Ryan White HIV/AIDS CARE Act-funded program at a crossroads. But advocacy strategies are afoot, not only to work toward continuation of Ryan White funding past its September 30 expiration, but also to promote a long-overdue implementation-science agenda to maximize the effectiveness and efficiency of HIV services.

Since its inception in 1990, the Ryan White program has been the “payer of last resort” for hundreds of thousands of low-income people living with HIV/AIDS in the U.S. Over the years, Ryan White–funded organizations have trailblazed the patient-centered medical-home model by integrating expert HIV medical care coordination with innovative psychosocial and supportive programs, such as housing, transportation, and meals.

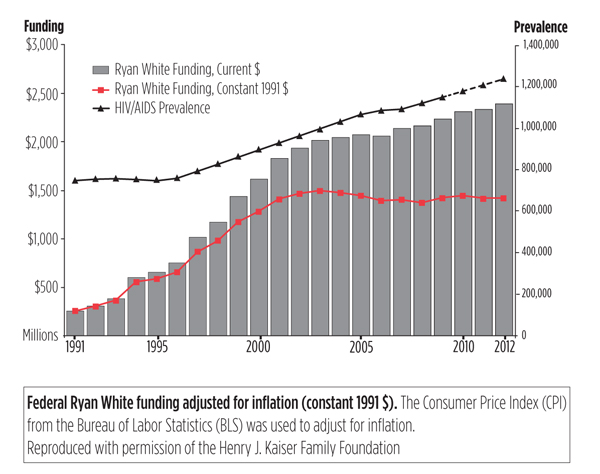

Given the ongoing congressional budget battles and deepening, polarizing debate on social programs and entitlement spending, many advocates are wary about pushing for a full-fledged reauthorization this year. Alternatively, since the last reauthorization bill does not have a sunset clause (a provision indicating that the CARE Act will cease unless legislative action is taken to extend the law) some advocates are pushing for a much quieter process—simply extending funding for Ryan White activities through the regular budget and appropriations process. However, this strategy may also be problematic in this fiscal climate, as funding for the program has already failed to keep pace with inflation and the increased need for services over the last decade (see figure).

Additionally, the pressure is on Ryan White organizations to adjust to a changing health care service- and delivery market. For those in states where governors have opted for Medicaid expansion, the task will be to remain relevant in places where more people will have access to insurance coverage. This may mean focusing on people with HIV who remain underinsured and uninsurable (e.g., undocumented immigrants) and expanding services beyond HIV/AIDS. Conversely, the working poor in states whose governors have opted out of Medicaid expansion will be worse off than they are now, as they will likely be ineligible for Medicaid or subsidized private insurance. This situation will undoubtedly exacerbate persisting ethnic, racial, and geographical disparities in the HIV epidemic, but it will also bring political immediacy to the dire need to expand Ryan White funding for essential wraparound prevention, treatment, care, and supportive services in those areas.

Over the course of this year, TAG staff will be looking at some of the key structural drivers of the HIV epidemic to make the case for increased research to promote better prevention, care, and service-delivery models. We are working with federal and state advocates to identify gaps in the National HIV/AIDS Strategy, Affordable Care Act implementation, and Ryan White program to expand and safeguard access to medical care for all Americans living with HIV in the coming years.•