Hepatitis C is now curable. Now all we need is surveillance to monitor it, global funding to fight it, and targets set to address it

By Tracy Swan

The first global targets for eliminating hepatitis C virus (HCV) will be set by the World Health Organization later this year. It’s about time: although HCV is preventable and curable, it kills 700,000 people annually and continues to spread among millions more. At least 185 million people worldwide have been infected with HCV, although data on the epidemic’s scope and spread are sketchy. This inadequate surveillance has made it easy to ignore hepatitis C, and difficult to secure and allocate sufficient resources to save lives.

The best and worst of the situation—dramatic improvements in treatment in the face of a rapidly rising death toll—have ignited a global movement to address hepatitis C. The treatment revolution officially began in 2011, when proof-of-concept for an interferon-free cure was established. Since then, hepatitis C drug development has moved at breakneck speed.

Oral combinations of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) have cured over 90 percent of people in clinical trials, including people with cirrhosis or HIV/HCV coinfection. These DAAs offer great promise for a global public health approach to hepatitis C: using the same drugs for everyone, for the same length of time.

The response to HCV among women and children has been pitiful. Globally, 1.5 million to 12 million pregnant women have hepatitis C, and the vertical transmission rate ranges from three percent to 10 percent—possibly higher if the mother is also HIV-positive, especially if she is untreated. At present, there is no way to prevent vertical transmission.

As for the safety and efficacy of HCV treatment in children, trials are lagging. However, the first interferon-free pediatric HCV treatment trials are now opening in the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, Germany, Italy, and the Russian Federation.

Target DAA Regimen Profile Will Be:

safe and tolerable; preferably ribavirin-free (Ribavirin cannot be used in people with unstable heart disease or during pregnancy; it causes birth defects and can be fatal to unborn babies. It also has many side effects, including anemia.);

effective and potent: must cure ≥90 percent;

universal: can be used for all HCV genotypes; for people with HIV/HCV, cirrhosis, and kidney disease; during pregnancy and nursing; and in pediatrics and the elderly;

simple and easily delivered/administered: minimal pre-treatment testing and on-treatment monitoring needed; fixed-duration (preferably ≤12 weeks); once-daily (fixed-dose combination preferred); no food requirement;

affordable; and

stable at different temperatures.

Access, Access, Access

There are several barriers to HCV treatment scale-up—the most significant being high drug prices. In low- and middle-income countries, patent protection allows pharmaceutical companies to control where generic versions of their drugs are sold, through voluntary licensing (VL) agreements.

Many middle-income countries—including China, home to at least 30 million people with hepatitis C—have not been offered VLs, although they bear the brunt of the HCV epidemic. These countries are left to use legal challenges, such as blocking patents, issuing licenses themselves (called compulsory licensing), or purchasing drugs from another country, where affordable generics are available (called parallel importing).

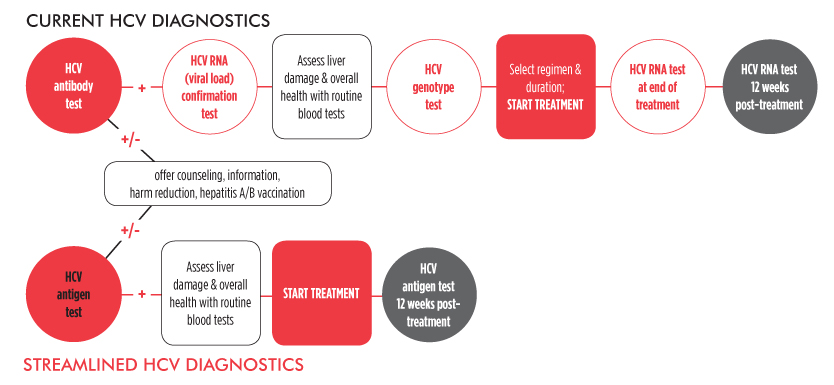

Scaling up HCV treatment is only one piece of the elimination puzzle. Diagnostics must also be simplified. Currently, diagnosing HCV is a complex, expensive, and inconvenient multi-step process. However, it may be possible to streamline HCV diagnostics and pre-treatment assessments in resource-limited settings.

Evidence to inform and support simplification of HCV diagnostics and monitoring—before, during, and after treatment—continues to evolve, including a handful of important studies featured at the 2015 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) in Seattle.

Unlike the interferon treatment days of yore, it may now be possible to treat hepatitis C without measuring pre-treatment viral load, or monitoring viral load responses during treatment—or at the end of it. Eliminating these tests will simplify treatment in resource-limited settings, ultimately saving time and money for patients and providers.

David Wyles from the University of California at San Diego and colleagues analyzed treatment outcomes among more than 2,000 participants in AbbVie’s PEARL, SAPPHIRE, and TURQUOISE trials (of ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir and dasabuvir, with or without ribavirin), including people with HIV/HCV or cirrhosis. They found that people were just as likely to be cured, whether it took two, four, six, or eight weeks of treatment to suppress HCV—and regardless of their pre-treatment hepatitis C viral load.

Viral-load test results at week four and at end of treatment (EOT)—a mainstay of HCV treatment monitoring—do not always predict the outcome of HCV treatment. Nearly everyone becomes undetectable within weeks of starting DAAs, but some people relapse within weeks of finishing treatment. In effect, early responses do not predict treatment success, nor do they predict treatment failure with DAA regimens.

Most people with detectable virus at week four will be cured, according to Sreetha Sidarthan from the Institute of Human Virology in Baltimore and colleagues, who analyzed results from the ERADICATE and SYNERGY trials of sofosbuvir-based regimens. Of the 17 people with detectable RNA at week 4 in SYNERGY, 100 percent were cured. In ERADICATE, 32 of 50 people had detectable HCV RNA at week 4; ultimately, 31 of the 32 were cured. EOT testing did not reliably predict cure either.

Researchers have speculated about why HCV may be detectable at the end of treatment in people who are actually cured. One such theory developed by Thi Huyen Tram Nguyen of the French Institute of Health and Medical Research and colleagues suggests that some defective virus lingers after HCV treatment has stopped production of new virus. This virus cannot infect liver cells or reproduce, but persists after treatment is finished, only to die off a few weeks later.

Picking a single HCV regimen that suits all, including people living with HIV, has become easier. In clinical trials, cure rates are just as high for people coinfected with HIV and HCV as for people with HCV alone. An important consideration, however, is drug-drug interactions. Since most HIV-positive people will be using DAAs with HIV treatment, interactions with antiretrovirals (ARVs) need to be managed—or avoided.

The once-daily combination of sofosbuvir and daclatasvir—expected to be approved in the United States later this year—is ARV-friendly. Sofosbuvir can be used with all ARVs except tipranavir/ritonavir. Although daclatasvir dose adjustments are needed with certain ARVs (atazanavir and efavirenz), no change in dosing is needed with other boosted HIV protease inhibitors (darunavir and lopinavir), all nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, certain non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (nevirapine and rilpivirine), and the integrase inhibitors raltegravir and dolutegravir.

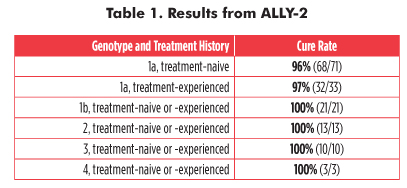

Sofosbuvir and daclatasvir also boast very high cure rates in HIV/HCV-coinfected individuals. In ALLY-2, a phase III evaluation of this regimen, 203 coinfected participants were treated for eight or 12 weeks, according to genotype and treatment history. At CROI, David Wyles and colleagues reported that 97 percent of the 12-week group were cured. In the 8-week group, 76 percent of treatment-naive study participants with HCV genotype 1 were cured.

Daclatasvir and sofosbuvir were safe and effective for HCV genotypes 1, 2, 3, and 4, regardless of treatment experience or liver damage (although cure rates were slightly lower in people with cirrhosis) (see table 1). But more information is needed in non-1 genotypes, especially in people with genotypes 5 and 6, and in people with genotype 3 and cirrhosis—for whom cure rates have reached only 60 percent. Unfortunately, there were only 26 people with non-1 genotypes in ALLY-2; none had G5 or G6. Data on other pangenotypic combinations are expected later this year.

More good news for people with HIV/HCV coinfection came from ION-4, a 335-person trial of co-formulated sofosbuvir and ledipasvir in people with HCV genotypes 1 and 4. Susanna Naggie from Duke University and colleagues reported that 96 percent of study participants were cured after 12 weeks of treatment. Study participants’ ARV regimen options were limited to those containing efavirenz, rilpivirine, or raltegravir, plus tenofovir and emtricitabine (because of a known drug interaction between sofosbuvir/ledipasvir and tenofovir, renal function was carefully monitored during this trial).

Treatment history or cirrhosis did not lower cure rates, but race did—unlike trials of sofosbuvir/ledipasvir in HCV monoinfection. Naggie and colleagues noted that all 10 relapses occurred in black participants, and the cure rate was lower (90% vs. 96%). There were no differences in HCV drug levels by race or ARV regimen, or in people who relapsed versus people who were cured. More research will help to explain and, we hope, override the difference in response rate.

On the treatment front, progress against HCV has been astounding. But even the best DAAs—once they are universally affordable—and the simplest diagnostic and monitoring tools aren’t enough. Political will and resources will be essential to achieving global hepatitis C elimination targets once they are finally established. The infrastructure to make good on these goals must be created—or expanded. The structural barriers that have allowed this epidemic to flourish—such as criminalization of gay people, people who use drugs, and sex workers—must also be eliminated.•