The time has come for U.S. tuberculosis programs to have full access to the Stop TB Partnership’s Global Drug Facility procurement and stockpile safety nets

Kenyon Farrow

Generic drugs can be credited with saving millions of lives by allowing for life-threatening infectious diseases to be treated and cured affordably. However, access to these drugs still leaves a lot to be desired in many countries. These include the United States, where low-prevalence diseases like tuberculosis (TB) are at the mercy of limited market competition among generic drug makers, which can result in drug shortages when manufacturing or distribution problems arise. Without a national procurement or stockpiling strategy in place, the United States will likely continue to see shortages of anti-TB drugs, which tripled from 2007 to 2012.

U.S. taxpayers support an institution that is helping to solve the stock-out problem internationally: the Global Drug Facility (GDF). The GDF is one of the most efficient operations for managing a global supply chain of safe, effective, and affordable TB drugs in low- and middle-income countries. The United States, however, has no such procurement system, and all but three of the drugs distributed by the GDF are unavailable to TB patients in the United States.

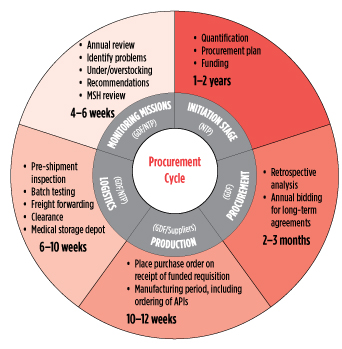

The GDF was created in 2001 by the World Health Organization (WHO) Stop TB Partnership. It serves 129 countries through technical assistance in management and monitoring of TB drug use, as well as procurement of high-quality TB drugs at low cost. The GDF purchases TB drugs, diagnostics, and medical equipment from various manufacturers who all have met the quality assurance guidelines of its funders, primarily the United States Agency for International Development and Canadian International Development Agency. To date, the GDF has delivered first-line TB drugs to 23 million people worldwide, with an average cost for a six-month course of first-line TB treatment of only US$17.40 (which includes commissions, quality control, insurance, and transportation). The GDF also has its own tracking system for procurement and supply-chain management (see figure).

Good planning ensures that quality medications can be delivered to the right people and at the right time. In particular, planning ensures that there are no stock-outs and patients are not cut off from lifesaving drugs. This figure illustrates the GDF’s supply-chain management cycle, actors responsible, and estimated time frames. Stock-outs aren’t limited to manufacturing delays—poor TB program planning and late disbursement of funds by governments and donors are also factors and factored into the GDF’s early-warning stock-out system.

Good planning ensures that quality medications can be delivered to the right people and at the right time. In particular, planning ensures that there are no stock-outs and patients are not cut off from lifesaving drugs. This figure illustrates the GDF’s supply-chain management cycle, actors responsible, and estimated time frames. Stock-outs aren’t limited to manufacturing delays—poor TB program planning and late disbursement of funds by governments and donors are also factors and factored into the GDF’s early-warning stock-out system.

GDF: Global Drug Facility

NTP: National TB Program

MSH: Management Sciences for Health

Source: World Health Organization/Stop TB Partnership

The United States had a resurgence of TB in the 1980s and 1990s as a result of the AIDS epidemic. However, there has been a substantial reduction in the number of people with active TB disease since the advent of antiretroviral therapy and a concerted effort to eliminate TB in the 1990s. But as TB incidence has decreased (now to about 10,000 cases per year), so has the number of drug manufacturers producing for the small U.S. market.

With so few generic drug manufacturers, if there is a problem with the production of an active pharmaceutical ingredient in just one manufacturing facility, it can cause a major stock-out for the entire market, sometimes lasting for months. As a result, cash-strapped state and local TB control programs have to spend additional time and money searching for alternative medications that may be less effective. They also have to report those shortages to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA); manufacturers themselves are supposed to do so, but once there’s a shortage, the damage is done until the problem is solved. Due to the lack of an effective warning system, the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association (NTCA) has created a database for TB programs to upload information about drug shortages, which in turn alerts the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the FDA. But it is a volunteer association, and this kind of strategy should be something a federal agency should manage.

For the last two years, TAG has been working closely with TB advocates from the American Thoracic Society, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, PATH, RESULTS, and the NTCA to work with the CDC, the FDA, and other U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) staff to raise the urgency around the issue of TB drug shortages in the United States, and to develop a strategy to address it. We’ve been advocating for the U.S. to adopt a national procurement approach that would create more market stability in drug supply and in cost, and provide advanced warning of manufacturing challenges that might result in a drug shortage (the GDF’s system can predict a shortage up to 12 months in advance). At a TAG-sponsored meeting held in January 2014, the GDF made a presentation to advocates and high-level government officials at the FDA, CDC, and Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority of HHS. In theory, the GDF could assist the United States with ending TB drug shortages, but there are several challenges moving ahead.

First, only three first-line TB drugs procured by GDF have been registered with the FDA. With so few active TB cases in the United States, there’s little incentive for generics manufacturers to pay the $64,000 application fee for what would be relatively low sales. More manufacturers need to be in the U.S. market. They are needed not only to help prevent drug shortages, but also to prevent price gouging in the event of supply problems. We are currently working with the FDA to develop some process for encouraging generic drug manufacturers to apply for FDA approval. Since all of the GDF manufacturers have met the quality assurance standards of stringent regulatory authorities around the world, there may be some way to fast-track the approval process.

In March 2014, the CDC confirmed that local TB programs may order the three drugs currently available from the GDF—capreomycin, cycloserine, and PAS. Since then, the GDF has also begun distributing two other drugs approved in the U.S.: rifabutin and bedaquiline. But a Department of Homeland Security regulation prevents local TB programs from importing those medications manufactured outside the U.S. (even though active pharmaceutical ingredients found in many generic drugs are not produced domestically). But ordering the treatments state by state creates other problems.

Individual state TB programs sporadically ordering products when in an emergency could be a drain on the GDF’s stockpile. If the GDF is not consistently monitoring U.S. drug supply, it becomes more difficult for them to anticipate supply levels and demand over time. As a result, they may have to pull TB drugs from existing supplies allocated to other countries in order to fulfill inconsistent orders from state TB programs in the United States.

In order to solve the problem of domestic TB drug stock-outs, we will need better coordination between the FDA, the CDC, and other regulatory bodies. Even though generic drugs have helped minimize TB drug costs, the ability to treat and cure TB still relies on the market, where supplies can run low and prices can spike, and on the existence of national programs that can negotiate prices, encourage manufacturers, stockpile medications, and actively monitor the manufacturing and supply chains to avoid shortages.

With an existing infrastructure and thirteen years of expertise, the GDF could be a great partner to U.S. agencies to ensure treatment access and market stability.•