We can’t end the viral hepatitis epidemics unless we end the war on drug users

By Annette Gaudino

“Unidentified Filipino male. Unidentified Filipino male. Unidentified Filipino female. Unidentified Filipino male…” It takes a long time to read 1,900 names, long enough to feel every inch of the concrete wall against my back. We had gathered outside the midtown Philippine Consulate to “die in”— dozens of activist bodies laid out under a large picture window through which a video of sandy white beaches and tropical flowers played on a loop. The protest of newly elected Philippine President Duterte’s extrajudicial killing spree, directed at suspected drug users and dealers, received international press attention and unleashed a torrent of invectives on the social media accounts of organizers. This was further evidence, if any was needed, that the so-called war on drugs has always been a war on drug users: individuals systematically robbed of their freedom and dignity—even their names.

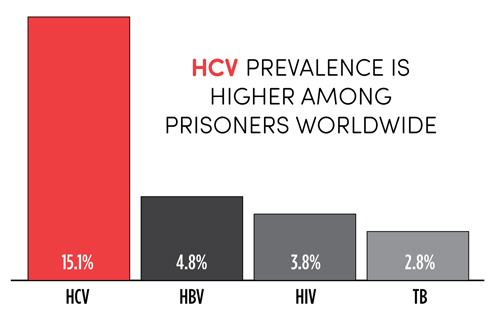

According to a new meta-analysis conducted by Kate Dolan, PhD (University of New South Wales), and colleagues on the burden of HIV, tuberculosis (TB), and Hepatitis C virus (HCV) among prisoners, there are 10.2 million incarcerated people worldwide, including 2.2 million in the US. An estimated 15.1% of prisoners worldwide have HCV and 4.8% have chronic Hepatitis B virus (HBV), which are higher prevalence rates than those for HIV (3.8%) and active TB (2.8%). In addition, 30 million prisoners transition between the community and prison each year. Research indicates that infection risk increases following release from prison, both for the formerly incarcerated and their sex and drug-using partners. Thus, to achieve the World Health Organization’s (WHO) goal of eliminating viral hepatitis as a public health concern by 2030, civil society has a duty to intervene where criminalization and incarceration conflict with sound public health policy.

Meeting the challenges of access, equity, and rights were the animating themes of the 2016 International AIDS Conference in Durban. Participants in the Viral Hepatitis Pre-conference learned about the limits of using existing HIV infrastructure to implement the HCV response, and the need to think beyond the individual drug users. Presentations stressed that programs targeting individuals in isolation are unlikely to meet the challenge of eradicating viral hepatitis; rather, we must address individuals as members of social networks and larger communities. Although Durban 2016 highlighted the push to put key populations at the center of the HIV/HCV response, no one lives solely within a key population—and no population, no matter how marginalized, functions in isolation from other sectors of society. A person who uses drugs lives in a network of fellow users, but he or she is also a child, sibling, parent, student, employee, and neighbor; a member of an ethnic or racial community in a larger nation; and a peer to those who don’t use drugs, but who share a common sub-culture or interests. Social drivers such as poverty and attitudes toward drug use serve as the backdrop for struggles to prevent disease and manage health.

For drug users, the primary intersection of these identities and social drivers is the criminal justice system, which sets drug use and its comorbidities apart from other public health issues and systems. There is a misperception that incarcerated individuals in the US have an absolute right to medical care. In fact, the Supreme Court has placed the burden on prisoners to prove their serious medical needs were known to prison officials and deliberately untreated (Estelle v. Gamble, 429 US 97, 1976). Furthermore, the federal Bureau of Prisons guidelines triage care based on liver disease progression and recommends only voluntary screening. This screening policy acknowledges that lack of confidentiality and safety inside the prison walls make knowing your status a risk for violence, not unlike the early years of the HIV epidemic. In practice, however, this means only the sickest will be identified and treated, allowing progressive liver damage and continued transmission of the virus.

Regardless of a country’s overall GDP, prisons should be seen as resource-limited settings, with multiple financial and infrastructure barriers to care. Even with pan-genotypic drugs to simplify diagnosis and treatment, high prices render them a low priority for incarcerated individuals. Finally, you can’t run an HCV program without access to HCV RNA testing to verify treatment success, a significant barrier in many low- and middle-income countries with regards to the general population, much less the incarcerated population.

Robust harm reduction services are also needed to prevent de novo infection and reinfection, but there are legal and funding barriers that prevent the rollout of evidence-based interventions, including syringe exchange, opioid substitution therapy, safe injection facilities, and drug consumption rooms. In the US, the use of naloxone to prevent overdose is receiving growing acceptance among law enforcement, but interventions to keep drug users safe and healthy before they overdose are still considered to be too radical for use in the community, much less in prisons.

Still, those working with the hardest-to-reach populations continue to innovate, with programs in India giving users testing coupons to identify and treat whole networks, and national and local health ministries—in Punjab, for example—stepping up to provide low- or no-cost HCV cure. Peer support is critical for linking individuals to care and ensuring treatment adherence, with the Community Network for Empowerment (CoNE) drug users’ union in Manipur, India, and VOCAL in New York serving as two effective examples. Following the model pioneered by Partners in Health for TB treatment in Haiti, observed treatment programs may also help address the complex support required to achieve treatment success among those with substance use disorders. In fact, if elimination is the goal, those at highest risk for reinfection need treatment the most.

As numerous public health champions have said repeatedly, we must take morality out of public health. Treating and curing active drug and alcohol users, and removing prison as the primary intervention for those with substance use disorders, must be at the center of the global response to viral hepatitis. Simply put, we must value people with HBV and HCV—including prisoners and illicit drug users—enough to keep them alive.•