We will not end HIV as an epidemic without the expertise and leadership of Black and Latino gay and bisexual men and transgender people of color.

By Jeremiah Johnson

In February 2016, the CDC issued a new report with a frustratingly familiar conclusion: if the current rates of new infections persist, approximately half of Black gay and bisexual men and a quarter of their Latino counterparts could become infected with HIV in their lifetime.

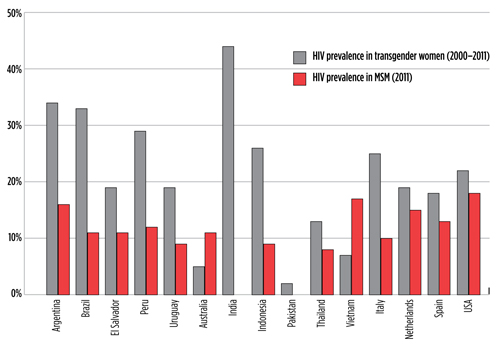

HIV prevalence estimates for transgender women in 15 countries from a systematic review of studies from 2000 to 2011, shown alongside 2011 prevalence estimates among gay and bisexual men and other MSM. In 11 of the 13 countries with both surveillance data sets available, the prevalence for transgender women is substantially higher.

Baral SD, Poteat T, Strömdahl S, Wirtz AL, Guadamuz TE, Beyrer C. Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013 Mar;13(3):214-22. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70315-8.

UNAIDS. Key Populations Atlas: People Living with HIV. AIDSinfo [Internet]. (date unknown) (cited 2016 September 13). Available from: http://aidsinfo.unaids.org/.

Wejnert C, Le B, Rose CE, et al. HIV infection and awareness among men who have sex with men—20 cities, United States, 2008 and 2011. PLoS One. 2013 Oct 23;8(10):e76878. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076878.

Hearing about racial disparities among gay and bisexual men, ad nauseam and without change, is maddening—but at least the story is being told. For transgender women and men, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has yet to produce any sort of substantial behavioral or surveillance data 35 years into the epidemic, rendering trans communities statistically invisible. The information that we do have from researchers outside of the CDC indicate that transwomen in the US, particularly transwomen of color, may be the most disproportionately affected group of all of the key populations in the US.

Given that we have known about these disparities for many years, if not decades, one might expect that those of us receiving a paycheck to work on HIV prevention in the US would be on top of our game when it comes to including Black and Latino gay and bisexual men and transgender men and women in new initiatives to help HIV-negative people remain HIV negative. In reality, however, the communities that are repeatedly overburdened when we discuss the problem remain consistently excluded and under-represented at almost all levels of our national HIV prevention response.

A recent analysis of data from 44 percent of US pharmacies conducted by Gilead, the pharmaceutical manufacturer with monopoly ownership of the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), found that 90 percent of Truvada-as-PrEP prescriptions went to men. In terms of race, 74% of PrEP prescriptions went to white people, with only 10 percent going to Black individuals—a racial disparity that appears to be growing over time. Although PrEP isn’t necessarily for everyone and uptake of PrEP is an imperfect indicator of prevention efforts, with around two-thirds of new diagnoses among men who have sex with men (MSM) occurring among men of color in 2014, we would hope that PrEP prescriptions would be proportionate. In terms of transgender women and men, they continue to be so invisible that even simple attempts to include them in the data on PrEP uptake have yet to be attempted by Gilead or the CDC, making it impossible to know how well we’re doing.

These disparities in PrEP outcomes and data collection are disappointing, and in terms of representation in PrEP efficacy and implementation research, our nation’s most affected communities no better off. Transmen typically do not exist in research, and transwomen, when included, are essentially misgendered and lumped in with studies focusing primarily on MSM. In iPrEx, the study that ultimately led to FDA approval of PrEP, a relatively small number of transwomen were included along with a large number of gay and bisexual men, with several transwomen dropping out or having challenges with adherence in the study. Follow-up analysis has indicated that the study design, which was clearly geared toward gay and bisexual men, may have created barriers to ongoing trans inclusion. Data from the study are no less sobering: no difference in new infections was observed between transwomen in the control arm and those receiving PrEP.

A PrEP demonstration project specifically geared toward transwomen and transmen in California was launched in April—six years after iPrEx yielded its final results. This significant delay in vital trans-related research has had substantial policy repercussions: PrEP use among transwomen and transmen hasn’t received as strong a backing from the CDC and the World Health Organization as other key populations, due to a lack of data proving effectiveness.

Inclusion and retention of gay and bisexual men of color in research, particularly Black men, is similarly dismal. Only 9 percent of participants in iPrEx were African American. In a large three-site US demo project funded by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, only 9 to 13 percent of those screened for participation identified as being African American, depending on how researchers defined race and ethnicity. Although other large demo projects in the US are ‘targeting’ men of color, only HPTN 073 has been specifically focused on Black MSM. The results of that study have shown promise, but it was only funded to engage a modest 226 individuals through three sites.

We are aware of no study that is looking to specifically assess the needs of Latino gay and bisexual men, particularly those with differing levels of English comprehension and immigration status.

Given all we know in about HIV disparities, along with our own overblown talk about ending them, how is it that prevention research and services still so lopsidedly favor white cisgender men in America? Some of these poor outcomes are the product of many intersecting structural and social issues that are difficult to remedy, but under-representation issues in research, statistics, and funding are capable of being addressed directly by public health officials, academics, policy makers, and other powerful individuals in the national HIV prevention response.

The CDC could develop a comprehensive strategy for inclusion of transgender data and invest in it. The CDC, National Institutes of Health (NIH), and other federal agencies could commit to doing whatever it takes to find effective PrEP implementation in Black, Latino, and trans communities. Funding incentives could be built into all of the CDC and NIH prevention research grants for projects led by Black and Latino gay men and trans women and men. So why hasn’t this happened?

Conventional wisdom in HIV has for decades held that effective efforts cannot be built without direct involvement of affected communities. In 1983, a group of HIV-positive individuals attending a national conference on Gay and Lesbian health in Denver managed to pen one of the epidemic’s most enduring and important human rights documents. The Denver Principles unambiguously and unapologetically articulated the importance of self-empowerment and the inclusion of people living with HIV in all aspects of the HIV response. It laid the groundwork for the notion that there should be “nothing for us without us;” that the most affected communities should be included in leadership related to HIV-related policies, research, and service delivery. To this day, the bravery of those authors influences the way we address the ongoing pandemic and highlight the essential role of community.

As is often the case in US, however, that spirit of community representation appears to have favored those who are white and those who adhere to traditional gender expressions. In the national HIV prevention response, Black and Latino gay and bisexual men, as well as transgender men and women, appear to be woefully under-represented in high-level research and policy meetings, key leadership positions, and critical discussions. Even in newer initiatives that could potentially be more inclusive, these inequalities are perpetuated. In New York, for example, the task force convened in 2014 to develop a blueprint for ending HIV as an epidemic in that state reportedly included only one young gay man of color, one transgender man, and one transgender woman out of nearly 60 members. Similar inclusion issues in leadership and membership have been noted in the Fulton County Task Force in Georgia. In addition, community advocates have expressed concern in recent years that organizations led by Black and Latino gay and bisexual men and transgender men and women have largely not received CDC prevention funding.

Data are needed to assess just how bad these observed issues with diversity are. Although the essentiality of inclusion for white gay men has long been a foregone conclusion on the policy and research level, many may also argue that we can’t prove that increased diversity among government and researchers will lead to better outcomes. A fair point; it certainly is a challenging argument to prove definitively with current data, and we can hardly design an ethical randomized control trial to test out the effect of systemic racism and transphobia. Still, one can’t help but wonder if more diverse leadership might make a difference.

An opportunity to explore the great potential of diversified HIV leadership is upon us, however. U.S. presidential candidate Hillary Clinton recently committed to establishing a task force to develop a plan to end HIV as an epidemic in the US, similar to the one convened in 2014 by Governor Cuomo in New York. Should Ms. Clinton be elected, a commitment to finding highly qualified and diverse leadership in the task force could set an important procedural standard for how to best address HIV nationally. The task force could be the perfect high-profile opportunity to go beyond mere tokenism and ensure that gay, bisexual, and transgender people of color are appointed, recognized, and heard for their experiences, knowledge, and expertise—all of which are critical to stopping HIV as an epidemic. Bringing back the spirit of The Denver Principles just might make the difference in avoiding yet another plan that primarily helps white cisgender men, while ultimately contributing to growing disparities for the most overburdened communities.•