UPDATE: December 18, 2014

Sound Science of Redesigned STREAM Trial

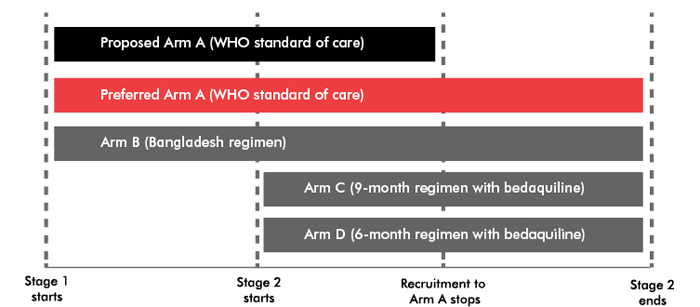

Investigators of the STREAM trial have successfully redesigned Stage 2 of the study to address concerns raised in the original article (below). Published in our Spring 2014 issue, this article argued that the safety and efficacy of two bedaquiline-containing regimens being tested in STREAM Stage 2 should be compared against the current World Health Organization standard-of-care, not just against the nine-month modified Bangladesh regimen, which is still undergoing clinical evaluation in STREAM Stage 1. Following publication, the funders of the STREAM trial (USAID), along with the trial’s principal investigators, sponsors (The Union), and the pharmaceutical company that developed bedaquiline (Janssen), entered into discussions with TAG and other activist groups—including the Global TB Community Advisory Board, the Community Research Advisors Group, the European AIDS Treatment Group, and the AIDS Treatment Activists Coalition. All stakeholders agreed to alter the design of STREAM Stage 2.

In the improved redesign, Stage 2 of the trial will continue enrolling some patients into the current standard-of-care arm. If Stage 1 of the trial fails to show that the nine-month modified Bangladesh regimen is not less effective than (non-inferior to) the WHO standard-of-care, the bedaquiline-containing regimens can still be compared to the current WHO standard-of-care in Stage 2.

The Union has also taken steps to strengthen community engagement in the STREAM trial by supporting activities at participating clinical trial sites. TAG is encouraged by the willingness of the investigators to take community input seriously and modify the trial’s design to address concerns about using a promising, but as yet unvalidated, short-course regimen as a control arm in place of the current standard of care.

Confirming the efficacy and safety of bedaquiline-inclusive regimens is a priority. Comparing them to unvalidated MDR-TB drug combinations in the planned STREAM study is not the way to go about it

By Mike Frick

They should have left well enough alone. The original design of a landmark clinical trial evaluating a shortened course of treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) was just what was needed to confirm its potential benefits over the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) standard of care. The clinical trial’s aim has since been conflated with another research priority—confirming the safety and efficacy of new MDR-TB drug bedaquiline—resulting in a study design that detracts from the importance of validating a tweaked Bangladesh regimen and may potentially undercut a scientifically sound assessment of bedaquiline in today’s MDR-TB armamentarium.

The Evaluation of a Standardized Treatment Regimen of Anti-Tuberculosis Drugs for Patients with MDR-TB (STREAM) study is the largest MDR-TB clinical trial in history. Sponsored by the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, STREAM will evaluate whether a standardized nine-month MDR-TB treatment regimen first studied in Bangladesh is noninferior to (not less effective than) the current WHO standard of care, in which treatment lasts for two years or more. The STREAM sponsors have now partnered with Janssen to add two bedaquiline-containing arms to the study. Janssen has signaled that these arms will take the place of a separate phase III trial of bedaquiline and will test whether the addition of bedaquiline can improve the Bangladesh regimen by replacing the injectable drug kanamycin or reduce the duration of MDR-TB treatment to just six months, all the while attempting to address important safety signals that arose during the phase IIb randomized controlled trial of the drug.

Shortening MDR-TB treatment would revolutionize the TB field. But the proposed design of STREAM downplays concerns about the Bangladesh regimen and may not provide the additional safety data on bedaquiline for which TB-affected communities have called. Without revisions to STREAM’s current design, the clinically unvalidated Bangladesh regimen may replace the current WHO standard of care as the foundation on which future knowledge of bedaquiline’s safety and efficacy will be based. This slippage from standard of care to presumptive alternative is especially troubling given the scientifically dubious origins of the Bangladesh regimen.

In 1997, a year when bedaquiline remained just an unproven compound in the preclinical wilderness, the Damien Foundation began a prospective cohort study in Bangladesh to see if the two-year duration of MDR-TB treatment could be shortened using novel combinations of existing drugs. The study, which took 12 years to complete, assigned patients to sequential cohorts, with regimen optimization along the way. The sixth and final cohort evaluation of a seven-drug regimen—gatifloxacin, clofazimine, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide throughout the nine-month treatment period supplemented by high-dose isoniazid, kanamycin, and prothionamide during the first four months—resulted in 87.9% of patients completing treatment without relapse, a remarkable outcome in a field where MDR-TB cure rates have ranged from 11 to 79 percent.

Results were published in 2010, under the title Short, Highly Effective, and Inexpensive Standardized Treatment of Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis. Although the regimen was short and inexpensive, the title of the paper took significant scientific liberties in deeming it a “highly effective standard,” considering the observational nature of the study and major flaws in its design and conduct, notably:

- Cohort sizes were not predefined, a decision the study authors justified with the odd statement that “ethical concerns always overrode statistical power considerations.” In fact, appropriate statistical power constitutes an essential component of ethical research since studies not powered to produce scientifically valid results unnecessarily place participants at risk.

- More eligible patients chose not to participate than to participate (578 vs. 486), but for unknown reasons, posing a profound risk of selection bias.

- Cohorts were enrolled sequentially, meaning that the various regimens were studied during different periods of time. During the twelve years of the study, Bangladesh increased its human development index score (a composite measure of a country’s development status that combines health, income, and education indicators) by 28 percent and raised life expectancy at birth by six years, thereby creating a cloudy picture about how evolving socioeconomic forces in the country might have influenced the more favorable results seen in the later cohorts.

STREAM was originally designed to validate a modified version of the Bangladesh regimen—gatifloxacin will be replaced with moxifloxacin—by comparing it with the current WHO standard of care under the more stringent criteria of a randomized controlled trial. With bedaquiline entering STREAM, the trial will now include two stages. Stage 1 will evaluate the noninferiority of the Bangladesh regimen (arm B) to the WHO standard of care (arm A). Stage 2 will assess whether the nine-month bedaquiline-containing regimen (arm C) is superior to the Bangladesh regimen and, as an exploratory endpoint, test whether the six-month bedaquiline-containing regimen (arm D) is noninferior to the Bangladesh regimen.

This raises several ethical and scientific concerns. Stage 2 will likely complete enrollment before investigators know the results of Stage 1. If the Bangladesh regimen proves inferior to the WHO standard of care, then patients in stage 2 will have been randomized to arms C and D in vain. Safety of bedaquiline remains a secondary endpoint in stage 2, even though clarity on bedaquiline’s safety profile is arguably the most sought-after information given the higher mortality among patients receiving bedaquiline in Janssen’s phase IIb study.

Addressing these concerns will require revisions to the STREAM protocol.

TAG and Global TB Community Advisory Board guidance to the STREAM study investigators includes enrolling patients in arm A throughout the duration of the trial, powering the trial to allow for multiple comparisons (arm B vs. arm A; arm C vs. arm A; and arm C vs. arm B), and establishing safety as a primary endpoint during stage 2 of the trial.

Both the International Union and Janssen bear responsibility for enacting these revisions and setting the trial on sounder ethical and scientific footing. The additional resources required to continue enrollment in arm A throughout the duration of STREAM should be assumed by Janssen, which has a commitment to conduct confirmatory trials of bedaquiline’s safety and efficacy under the conditions of bedaquiline’s accelerated approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. For its part, the International Union must create avenues for meaningful community engagement on these controversial design questions. While STREAM investigators have allowed TAG and the Global TB Community Advisory Board to review the protocol and issue suggested protocol revisions, the International Union lacks the structured community engagement programs seen at other TB research networks. The absence of community engagement is unacceptable given the trial’s potential to dramatically reshape clinical practice.

STREAM offers an unparalleled opportunity to advance MDR-TB treatment, but the proposed design has allowed excitement about treatment-shortening to leapfrog the science with little chance for community input.•