Generic treatments for HIV, viral hepatitis, and cancer can be affordably—and profitably—mass-produced for broad, unobstructed availability

By Tracy Swan

TAG talks with Andrew Hill, senior visiting research fellow in the University of Liverpool’s Department of Pharmacology, about his group’s work exploring what it actually costs to profitably mass-produce generic drugs for HIV, viral hepatitis, and cancer. These estimates are based on the molecular structure, complexity, dose, and duration of treatment with each drug.

Achieving these prices—between $200 and $400 for a course of sofosbuvir and daclatasvir for hepatitis C virus (HCV), for example—is necessary to facilitate the mass scale-up of HCV treatment programs in low-, middle-, and high-income countries.

TS: What inspired you to look at production costs for hepatitis C treatment?

AH: By 2000, our group—and others—found out that HIV could be treated for about $500 per year. As soon as people realized that HIV treatment could be made for a dollar a day, universal access could be achieved. Now, over 15 million people are on treatment.

We decided to do the same thing for hepatitis. We looked at the doses and structures of the drugs and found that they were actually very similar to those used for HIV—often by the same research teams at the same companies. That was the inspiration.

The feedback I’ve had from doctors in almost every country is that prices for HCV drugs are too high everywhere; they have to come down in Brazil, in Thailand, in the U.K. We’ve got this opportunity to eliminate the HCV epidemic, and we are not doing it because the drugs are too expensive.

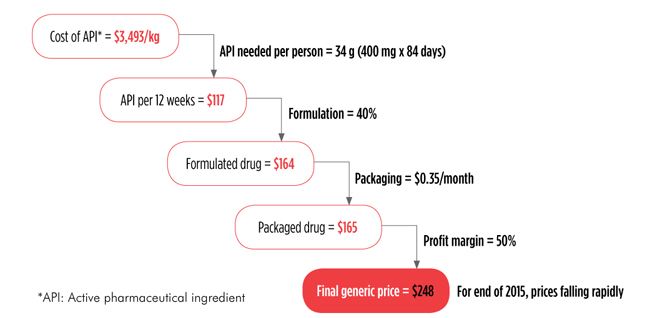

FIGURE: Current Costs of Production: Sofosbuvir

Source: Hill A, et al. Significant reductions in costs of generic production of sofosbuvir and daclatasvir for hepatitis C treatment in low- and middle-income countries (Abstract PE13/43). 15th European AIDS Conference; 2015 October 21–24; Barcelona, Spain.

TS: The initial U.S. launch price for sofosbuvir [Sovaldi, a drug that is the backbone of many HCV regimens] was $1,000 per pill. Thanks to work from you and your colleagues, we know that it can be profitably mass-produced for a little more than $1 per pill. It’s been really helpful for people doing hepatitis C treatment access advocacy to have this solid, credible information about production costs. We can now discuss the discrepancy between the price of a drug and what it costs to produce it.

AH: I agree, it gives people a term of reference to then say to a company, “If your drug is extremely cheap to make, and you haven’t done that much spending on research and development, how can you justify the prices that you are charging for your medicine?”

In the U.K., we probably have enough money—with the price that Gilead charges —to treat about 8,000 people a year. Now, there are 200,000 people with hepatitis C in the U.K. It would take 25 years to treat all of those people at the current prices.

TS: What about access to HCV treatment—and other drugs—in low- and middle-income countries?

AH: Companies will say, “we have authorized the use of our drug in 90 or 100 countries,” but if you look, some are tiny little islands in the Pacific or the Caribbean that hardly have any people living there at all. If you look at the number of countries where a company has actually filed and registered their drug—and where they have made sure that there is a generic producer—it might be only a small fraction of the original number of countries in their access programs. For example, Gilead claims that 101 countries have access to sofosbuvir. We’ve looked at the countries where sofosbuvir is actually registered and available through a voluntary license; this covers only a quarter of the hepatitis C epidemic—it is not universal coverage by any means.

I can see a time coming in the next 12 months where treatment with sofosbuvir and daclatasvir [Bristol-Myers Squibb’s drug, branded as Daklinza] will cost no more than $300 or $400 per person—we are nearly there. The prices are only going to come down over time and make it more affordable to treat people.

TS: You are looking into drugs for other conditions….

AH: After we did the analysis of hepatitis C drugs, we looked at entecavir, a drug used to treat hepatitis B. It was incredibly cheap to make—it almost cost more money to put the drug into a bottle and package it than the drug itself. Entecavir could cost $24 per person per year because the dose is only half a milligram per day; it’s like a grain of salt per person, per day.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors [used to treat breast cancer, lung cancer, liver cancer, and leukemia] are amazingly cheap, in a way that I had never anticipated. These lung cancer and breast cancer treatments are sold in the U.S. for well over $100,000 per person per year. They can be made for $100 or $200 per person per year.

Showing that cancer can be treated cheaply, as we found for HIV and viral hepatitis, could cause a real backlash. People cannot access the treatments that could save their lives because of the high profits that a company is demanding.

TS: Have you looked at production costs for tuberculosis drugs?

AH: Treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis [MDR-TB] is complicated. There’s a real complexity to TB treatment at the moment, which means that drugs are going to remain expensive. It involves a wide variety of drugs, produced in quite small quantities, to treat a selected group of people. You are not talking about treating millions of people for HIV with mass-produced drugs that are all the same.

With MDR-TB, the challenge now is to make treatment as uniform as possible so we have single combination treatments that then could be made cheaply and mass-produced in a more standardized way. We are not going to be stuck with this problem for that long—when we look at the cost of the newest drugs, like delamanid or bedaquiline, we believe that, fundamentally, they should be cheap drugs to make. This depends on producing large qualities of drugs, to treat large numbers of people. We haven’t had negotiations with the right governments yet to ensure the orders of a large enough supply to get prices down.

TS: What about tenofovir and TAF for HIV treatment and prevention?

AH: If you go to South Africa to buy a year’s supply of tenofovir, it will cost about $60—just above $1 per week. It is going to go off patent soon; by the end of 2017 or early 2018, you should be able to buy generic tenofovir very cheaply.

Now, Gilead is trying to sell a version of tenofovir called TAF [tenofovir alafenamide], by claiming that it has a better safety profile in terms of bone loss and kidney function. If you look at the difference in bone loss between normal tenofovir and TAF, it occurs within the first six months of treatment. In the START study, that difference had no clinical significance at all.

With any drug, you have to find out the safety profile in the long term. There are a lot of things that we don’t know about TAF. Other drugs can lower its concentration and might lower its efficacy. It’s quite a fragile drug in terms of drug-drug interactions, unlike normal tenofovir. TAF might have some problems down the line, when it is used in real-life studies and outside of phase III clinical trials.

We know a great deal about normal tenofovir. If someone takes normal tenofovir, in the first few months of treatment they will get a slight reduction in bone density and a slight change in kidney function—which may worsen over time. It is not clear whether TAF will have less kidney toxicity than normal tenofovir over time.

TS: How would you like to see some of your work used by activists and other people who are deeply concerned about drug pricing?

AH: In the United Kingdom, we now have people buying drugs through buyer’s clubs, for PrEP [HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis] or to be cured of hepatitis C. It is a last resort and unfortunate that we have to do this. But if it is a choice between buying a drug from a recognized generic supplier in India—which supplies drugs all over the world—or having nothing, the benefit of generic drugs is going to outweigh the risks for many people. We have to be careful to make sure that any drugs coming in are from authorized suppliers and that they have been approved by a regulatory authority.

People need to buy these drugs through established channels, to look for particular websites—we are working with a group called fixhepC.com. They have already treated over 1,000 people and cured almost all of them with drugs that they have secured themselves. If you work with established networks and you know that the drugs being distributed through those networks are curing people, you’ve got a bit more assurance that you are going to get a supply of good-quality drugs. Just buying them randomly on the Internet is not a good idea, because you don’t know where the drugs are coming from.

TS: We often hear that these profits are essential for innovation.

AH: Gilead spent 11 or 12 billion dollars on sofosbuvir and a maximum of $500 million on the clinical trials program. So there you have about $12.5 billion. By the end of 2015, Gilead had already sold $31.5 billion of Harvoni and Sovaldi. So they have a profit of just under $20 billion—for drugs with another 15 years of patent life.

The average pharmaceutical company will spend 70 to 80 percent of profits on marketing, advertising, and lobbying governments—and put the intellectual property of a drug in Ireland to avoid paying taxes.

I’d love it if pharmaceutical companies genuinely spent the majority of their profits on research and development and then produced new drugs. Then I wouldn’t be protesting.