By Jeremiah Johnson

Since 2014, several states, cities, and counties have announced plans to End the Epidemic (EtE), with many more preparing to announce their own initiatives in 2018. In New York, early successes have emerged in the most recent surveillance data (see: “New York State EtE Campaign Update: Successes & Challenges,” and several other jurisdictions are seeing the benefits of EtE plan implementation. However, a number of common challenges have become apparent across different jurisdictions. Here, leaders and experts in EtE planning processes share their perspectives on some of the most common roadblocks.

Galvanizing Community-Based Organizations and Avoiding Turf Wars

Community mobilization is at the heart of the EtE process. But galvanizing community leadership is challenging. Advocates may feel skeptical after previous grandiose initiatives produced limited results, or there may be a perception that the community lacks the resources or the ability to exact ambitious change.

“Every group that I’ve worked with knows their community has unique challenges and is significantly different from any other community that has embarked on the EtE journey,” shares Jaron Benjamin, Housing Works’ Vice President of Community Mobilization and National Advocacy, who has consulted with several EtE jurisdictions. “But the challenge is that some groups assume that their uniqueness means that they’ll never be able to demand action from their government in a meaningful way.”

Decades of competing for scarce resources may also dampen collaboration between community entities that are trying to protect their turf. “That has been a major challenge for the [Ending HIV in Houston] plan,” says Venita Ray, Public Policy Manager at Legacy Community Health and one of the leaders of the Houston EtE process. “I believe there is still reluctance to embrace the concept that ending the epidemic is possible, and most entities are still focused on testing and treating and not engaged in strategic discussions addressing the real core issues like racism, poverty, etc. We have had to spend additional time re-starting community engagement via our END work groups and strategic assignments of co-chairs from various community-based organizations (CBOs) to encourage involvement and shared leadership.”

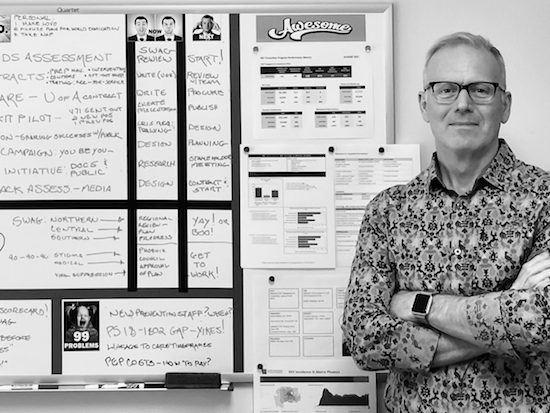

John Sapero, Office Chief of the HIV Prevention Program in the Arizona Department of Health Services and a key figure in the Arizona EtE process, highlights the challenges outside of urban areas. “Rural agencies were reluctant to invest the energy without a return. During our planning process, our stakeholders were adamant that we establish regional plans and funding allocations. It was a ton of extra work, but we created three regional plans. The goals and objectives are really no different for each region, but the implementation strategies really capitalize on the strengths of the local CBOs and AIDS service organizations (ASOs). ‘By us, for us’ strengthened regional collaborations and buy-in.”

Jaron Benjamin, Vice President of Community Mobilization and National Advocacy, Housing Works

Photo credit: Nick Childers

Ensuring All Affected Communities and Key Stakeholders are Engaged

Engagement of ASOs and CBOs does not always mean that the most affected communities in a jurisdiction are participating in leading the initiative, which can significantly limit the benefits of community mobilization in the implementation phase. From the start, a jurisdiction should have a plan in place to foster leadership from people living with HIV, communities of color, and transgender populations. Although building inclusive movements will be uniquely challenging in each jurisdiction, experiences in Arizona and Houston provide some insight.

According to Mr. Sapero, “We engaged these communities by bringing in nationally recognized CDC technical assistance providers to facilitate multiple planning activities dedicated to each population. This really energized our stakeholders, especially women, to get commitment from community and faith leadership.”

“In Houston, we have engaged in a number of initiatives with PLWHA [person living with HIV/AIDS] and other marginalized communities with mixed results thus far,” explains Ms. Ray. “We have ensured involvement of the HIV community by linking our efforts with other HIV leadership efforts. We also require one of the co-chairs to be a PLWHA. We were able to get funding to provide stipends to PLWHA to provide trainings to task forces on using people-first language.”

Establishing Equitable Transparent Partnerships with Health Departments

Although community leadership is critical, close partnership with local and state health departments is also essential for EtE success. But pre-existing power dynamics and differing motivations can interfere with collaboration.

“The health department has different interests than the community groups, and even if those interests aren’t nefarious, it means that there will typically be some information withheld or that the community wants to go further than the health department feels able.” Mr. Benjamin explains. “And that’s fine; in most community and government partnerships, some tension is healthy and necessary because of the power differential between the two.”

Mr. Sapero highlights the importance of health department transparency and accountability in establishing partnership. “Our planning activities were designed to bring governmental, private, and community-based organizations, PLWHA, and other stakeholders to the table as equals. We’ve committed to reporting our performance metrics on time, provide high-level programmatic reporting, and continually share the work of our partners with each other. More importantly, I believe our commitment to EtE energized many of our stakeholders.”

Venita Ray, Public Policy Manager, Legacy Community Health

Photo credit: KHOU-TV

Perceived Competition with Other HIV/AIDS Plans and Initiatives

EtE planning is unique in its combination of ambitious targets, community leadership, focus on structural drivers, and emphasis on implementation. However, no planning occurs in a vacuum, and integrating the EtE process into existing initiatives, including HRSA/CDC-required state Integrated Prevention and Care Plans, is challenging. Mr. Benjamin agrees, noting, “almost every jurisdiction that we’ve worked with had some sort of plan for responding to the HIV epidemic, and, to some extent, the more creative and innovative ideas had been passed over. The trick is to understand that a successful EtE effort isn’t reinventing the wheel, but building a bigger and more inclusive one.”

“I have to be honest and say our previous prevention and care planning efforts were nowhere near as performance and goal driven as our EtE plan,” says Mr. Sapero, introducing some of the synergistic approach that worked in Arizona. “No one had an issue moving toward something more visionary. We did a lot of front-end work to bring our three planning bodies into the same mindset before we started. Then, we started from scratch, aligning our plan development with the National HIV/AIDS Strategy, and using other EtE plans to guide us. We didn’t integrate the planning bodies, as we felt it was going to be a lot of work on top of developing our plan. We’re starting to explore integration now.”

Funding and Political Commitment

For emerging EtE jurisdictions in politically indifferent or hostile environments, understanding the role of political support and funding to achieve the recommendations in the plan should be an early focus in the planning process.

According to Mr. Benjamin, “I think it’s important to have an idea of who has funds to pay for your plan before you start writing the plan, and the best barometer of political buy in is whether you can get elected officials to fund the EtE plan. Sometimes elected officials have responded after public demonstrations, and sometimes after intimate closed-door meetings. I think you’ve got to consider every appropriate option to ensure that the responsible officials come through for the community.”

Ms. Ray explains the challenges and victories in Houston. “Our local governments are fiscally strapped for money and conservative government makes the issues difficult to build political support. Still, during the 2017 legislative session, we were able to prevent HIV criminalization legislation from being introduced, supported two syringe exchange bills and supported opt-out testing legislation. These are all policy recommendations in the END plan. With funding, our initial hope is to improve coordination of existing resources and beginning to solicit political support for funding initiatives.”

“We’re fortunate that ADAP 340b rebate funds are helping initiate some great work,” explains Mr. Sapero. “The mayor of Phoenix signed onto the Fast- Track Cities charter in 2016, the state health department has showcased our work to the media, and there’s currently a bill in the state legislature to formally recognize and adopt the plan. Several local representatives and county supervisors are supporting us as well.”

John Sapero, Office Chief, HIV Prevention, Program Arizona Department of Health Services

Photo credit: John Sapero

Lessons for Emerging EtE Jurisdictions

As reflected in the wisdom of Ms. Ray, Mr. Benjamin, and Mr. Sapero, much of the work to end epidemics begins with building effective relationships and avoiding the usual pitfalls between affected communities, CBOs/ASOs, and health departments. Emerging jurisdictions that invest time and resources into fortifying robust, transparent, diverse, and equitable partnerships between these key stakeholders are more likely to find success. An early focus on funding and political strategies, particularly with an intention to work synergistically with existing initiatives, will greatly facilitate implementation.

For the past year, as part of its Southern States EtE initiative, TAG has worked closely with three jurisdictions that have shown a strong commitment to redefining relationships between key stakeholders. Alabama, Louisiana, and Nashville, Tennessee, have held initial jurisdictional EtE meetings with a specific focus on inclusion and transparency; steering committees in each jurisdiction are now in the process of identifying ways to fill in any gaps in inclusivity and foster more open conversation between existing partners. In the case of Nashville, political support from the Mayor and early conversations about funding EtE planning and implementation are adding even more depth to the work of key stakeholders. TAG remains committed to documenting and advising emerging districts on these best practices in the south; including reaching out to support new cities, counties, and states that are prepared to embark on their own process.

For more information on EtE initiatives, please visit TAG’s website: treatmentactiongroup.org/ete