For people with drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB), generic linezolid may be a lifesaver. But only if quality-assured versions are available and affordable

Erica Lessem

As new drugs bedaquiline and delamanid offer renewed hope of treating DR-TB, doctors and programs are faced with the challenge of finding companion drugs to create regimens to which patients’ TB is still susceptible. Without other effective drugs, resistance may develop to bedaquiline or delamanid, and patients and communities have fewer chances of overcoming DR-TB. For this reason, interest in procuring linezolid has been increasing. For example, when Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) initiated a program in 2013 to facilitate compassionate use access to bedaquiline in Armenia, they gave all 23 patients linezolid. Linezolid is also important for patients with difficult-to-treat forms of DR-TB who cannot get newer drugs.

But Pfizer, which developed linezolid and markets it as Zyvox, has stymied access through restrictive pricing, research, and registration policies. Pfizer prices this antibiotic at a whopping US$154 per 600 mg pill (US$110,880 for a 24-month treatment course) in high-income countries like the United States. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), the drug’s price is similarly exorbitant—in South Africa, for example, linezolid is US$65 per pill (US$46,800 per treatment course). What’s more, Pfizer’s multiple patents on linezolid make it difficult for generics to enter the market: the basic patent expires in November 2014 in the U.S., but secondary patents on formulations could forestall generic competition until 2021.

One manufacturer, Hetero, has developed generic linezolid using a formulation that does not infringe on Pfizer’s secondary patents and has stringent regulatory approval from several European Union countries. Hetero’s linezolid is much cheaper than Pfizer’s, at US$8 per pill (US$6.90 when purchased through the Global Drug Facility or GDF) and is used in countries where Pfizer’s primary patent is not recognized. But cost is still a barrier: at US$5,760 a treatment course, this generic linezolid costs more than most multidrug regimens for DR-TB (usually US$1,670–5,000 in LMICs). It’s also more expensive than the costly new drug bedaquiline in some settings (US$4.79 per pill in low-income countries).

Increased competition from more generics manufacturers may help lower prices further. This may be on the horizon, as both Cipla and Macleods produce generic linezolid. However, neither product has quality assurance yet—an evaluation of its compliance with Good Manufacturing Practices by a stringent regulatory authority, the Global Fund’s Expert Review Panel, or the prequalification process of the World Health Organization (WHO). Additionally, both may infringe on Pfizer’s secondary patents, creating a barrier to their uptake in places where Pfizer has intellectual property rights, even once the basic patent expires.

The lack of regulatory approval or normative guidance on the use of linezolid for TB poses another major obstacle. Linezolid, approved for the treatment of other bacterial infections, has never received regulatory approval for the treatment of TB, nor is it on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines. Pfizer refuses to pursue registrations of linezolid for TB or to fund the research necessary to provide an evidence base for doing so. In fact, in 2013, Pfizer abandoned anti-infective drug research completely. In consequence, linezolid has never been tested in a large-scale clinical trial in people with TB. Data to support its use in TB come from one small clinical trial of people with extensively drug-resistant TB, from a number of nonrandomized studies of off-label use in DR-TB, and from in vitro and animal studies.

These limited studies indicate that, of last-resort drugs for TB, linezolid is one of the most effective. Linezolid does have severe side effects, such as peripheral neuropathy (nerve damage) and bone marrow suppression, which can lead to anemia and other health problems. These can be manageable and potentially mitigated by dose reductions. Nonetheless, the side effects limit linezolid’s optimal use to cases where potential benefit outweighs harm, such as in people with extensively drug-resistant TB, or those experiencing adverse effects from multidrug-resistant TB treatment. Larger, well-conducted, randomized controlled studies are required to confirm linezolid’s efficacy and to determine optimal dosing, timing, and duration of treatment to minimize side effects. These missing data will be crucial not only for guiding treatment with linezolid, but also for providing a clear evidence base for pursuing a TB indication for the drug.

Pfizer’s refusal to conduct these studies of linezolid has required governments, treatment providers, and nonprofits to pick up the slack. On the research side, the U.S. National Institutes of Health funded the above-mentioned small clinical trial of people with extensively drug-resistant TB (though Pfizer did contribute study drug). The nonprofit TB Alliance is conducting an early bactericidal activity study to look at the short-term anti-TB effect of various doses of linezolid. The South African Medical Research Council is funding a potentially groundbreaking study to look at linezolid along with bedaquiline and other drugs (we hope that Pfizer will contribute study drug for this trial as well).

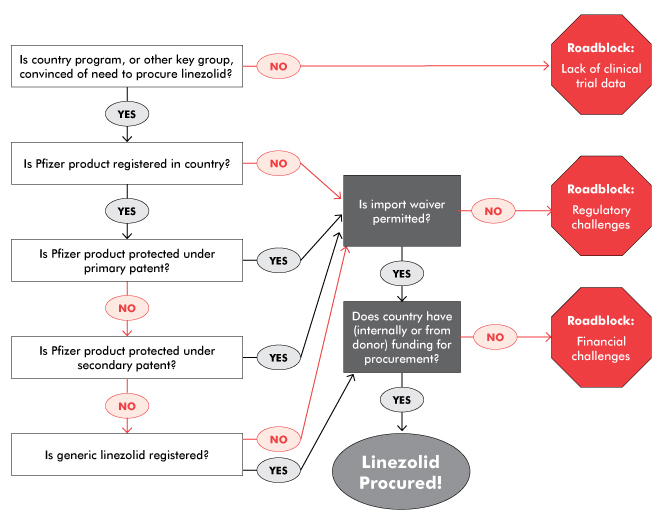

Similarly, Pfizer has neglected to pursue an indication for TB, even though registration issues normally fall under the purview of the original drug manufacturer. Overcoming regulatory hurdles has fallen on the shoulders of generics manufacturers, advocates, and national and nonprofit treatment programs, which have had to make a case for importing linezolid as it isn’t on the WHO’s or on national essential medicines lists for TB. The time-consuming work-arounds needed to import linezolid—particularly in its generic forms—are a drain on underresourced programs and likely contribute to the high cost of generic drugs and lack of interest in pursuing the TB market for generics.

For example, in South Africa, Pfizer’s high-priced linezolid was supposedly available in the public sector, but was rarely prescribed to patients with DR-TB due to its cost. MSF, which has been using Hetero’s linezolid worldwide, was unable to do so in South Africa, as the generic drug was not registered with the South African Medicines Control Council (MCC). In late 2013, MSF applied for permission to import the generic linezolid into South Africa under section 21 of the 1965 Medicines and Related Substances Control Act 101 (on the grounds of unaffordability of the Pfizer product). The MCC turned down the MSF application to import the Hetero linezolid, stating that affordability is not a consideration. MSF appealed this decision in early 2014, noting that previous section 21 applications were granted on affordability grounds, and that the state had a constitutional obligation to realize the right to health care for everyone in South Africa. When the MCC did not answer this appeal, MSF turned to litigation, which prompted negotiations outside of court. These negotiations led to permission for MSF to import generic linezolid for a renewable six-month period, provided that the quality of generic linezolid was confirmed and the MSF treatment protocol was submitted. This victory reduced the price of linezolid for MSF by 88 percent and is important for the patients who need the drug. It also sets a precedent for the importation of linezolid and other drugs under section 21 due to affordability reasons. However, it is not a widespread or sustainable solution, and required tremendous resources to achieve. Currently, the MCC is reviewing Hetero’s linezolid for full registration in line with the expiry of Pfizer’s primary patent, which would be a much less time-consuming and more durable solution.

In Moldova, which also faces a high burden of DR-TB, the national TB program and advocates had to face a less litigious but similarly indirect process to procure linezolid. Short of funding to purchase even the generic version, Moldova had to work with the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM) to redirect some funding to purchase Hetero’s linezolid from the GDF. In parallel, the Moldovan TB program had to appeal to the national drug regulatory authority to import Hetero’s linezolid, which was not yet registered in Moldova. Fortunately, as the product has a quality certificate, the regulatory authority granted permission. Nonetheless, it still took over six months for the linezolid to arrive in Moldova. Again, full registration of the drug would have expedited access to this important treatment.

As Karyn Kaplan and Tracy Swan note in “The Road to Treatment Access,” generic competition is essential to bringing down prices. In order to generate that competition and allow programs and patients to benefit from it, the right conditions need to be in place. These include unrestrictive intellectual property policies, sound evidence bases, and widespread registrations. In linezolid’s case, Pfizer has an ethical obligation to conduct proper research on the drug for use in TB to guide clinical care, clarify the market, and facilitate registrations and a TB indication. Pfizer should also voluntarily license linezolid, or at least not enforce patent rights, especially in the TB market in which they remain uninterested; this would facilitate the entry of Cipla, Macleods, and others. Cipla and Macleods should both seek quality assurance and stringent regulatory approval to facilitate the importation of their drugs and inclusion in the GDF catalogue. Rapid registration of generic linezolid in countries with high burdens of DR-TB is also important to speed procurement and reduce the burden on programs created by time-consuming and unsustainable import waivers and other work-arounds.

While Hetero’s product offers a glimmer of hope for programs to purchase linezolid without paying Pfizer’s exorbitant prices, more research, further price reductions, and widespread registration are urgently needed to improve access. In the meantime, programs and generic drug manufacturers can implement creative legal, financial, and regulatory solutions to get linezolid to those who need it.

For more information on linezolid’s safety and efficacy, see TAG’s recently released An Activist’s Guide to Linezolid.•