Effective responses to the burgeoning hepatitis C pandemic requires solidarity between the global North and South

By Bryn Gay

We can now cure the hepatitis C virus (HCV) with a coformulation of drugs that yields sustained virologic responses for all genotypes. Epclusa (sofosbuvir/velpatasvir), however, joins the ranks of other high-cost direct-acting antivirals that are inaccessible to the majority of the 150 million people living with chronic HCV around the world. Treatment activists need to escalate their advocacy and political pressure, draw on lessons from the AIDS movement, and emphasize conscientious solidarity among countries of the global South, as well as across countries in the North and South, to make universal generic access a reality.

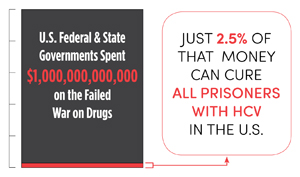

Epclusa, approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in June 2016, is a game-changing medication that is administered orally once a day for 12 weeks and reduces the need for genotype diagnostics, thereby saving money for cash-strapped budgets in lower- and middle-income countries. However, the $74,760 list price for Epclusa is expected to create enormous barriers to access. Public payers and private insurers in the US alone are limited in how many patients they can cover. By contrast, the $1 trillion failed drug war could have funded Epclusa treatment for 13.4 million people—four times the number of patients in the US. Adding to the public outcry, analyses by Andrew Hill of the University of Liverpool and his colleagues indicate that sofosbuvir can be produced with a 50% profit margin for as little as $62; thus, the current pricing of the cure is not justifiable.

Epclusa, approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in June 2016, is a game-changing medication that is administered orally once a day for 12 weeks and reduces the need for genotype diagnostics, thereby saving money for cash-strapped budgets in lower- and middle-income countries. However, the $74,760 list price for Epclusa is expected to create enormous barriers to access. Public payers and private insurers in the US alone are limited in how many patients they can cover. By contrast, the $1 trillion failed drug war could have funded Epclusa treatment for 13.4 million people—four times the number of patients in the US. Adding to the public outcry, analyses by Andrew Hill of the University of Liverpool and his colleagues indicate that sofosbuvir can be produced with a 50% profit margin for as little as $62; thus, the current pricing of the cure is not justifiable.

We have human rights obligations and we must invoke legislation, especially those that frame national strategies for HCV elimination. Activists can point to UN-ratified conventions and agendas that affirm the right to health care to demand access to the cure (see Mike Frick’s “Science and Solidarity”. A comprehensive human rights approach is based on equality (treatment should not depend on income level), destigmatization and humanization of all people living with HCV (everyone should have access, including people who inject drugs, prisoners, Vietnam veterans, indigenous peoples, and those living in remote communities), and the value of medicines as a global public good (taxpayer-funded drugs should remain in the public domain for everyone to benefit).

The HCV movement requires the building of solidarity across borders because collective, cooperative actions are more powerful and resilient than individual ones. Universal rights to health can connect local struggles with international patient networks. Each struggle needs to be autonomous in how it employs strategies according to local conditions, but can gain strength by uniting with global movements.

HCV activism can be informed by lessons from the AIDS movement:

- The cure to hepatitis C exists; a curative vaccine for hepatitis B virus (HBV) may be next. As we have seen with antiretrovirals (ARVs), breaking the monopoly and enabling generic competition can dramatically lower prices.

- A multitude of activists, including people living with HCV, HBV, liver cancer, and HIV, as well as related health and human rights groups, can strengthen efforts to resist the enclosure of the medicinal commons.

- ‘Inside/outside’ strategies must be deployed. Provocative, non-violent civil disobedience and clever use of the media can put HCV on the national agenda. They must be paired with informed patients who can demand expedient drug and vaccine development, regulatory reform, and stable funding. Activists must become their own specialists and challenge the exclusive control of treatment research held by pharmaceutical corporations.

- Patients need to be included in health policy decision-making.

- Peer-support programs reach peers who use drugs and effectively link them to testing, treatment, and care.

- Activists must demand funding and preservation of civil society space to protect this human right.

Solidarity in the global South—countries predominantly in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Pacific, which are lower and middle income—and between the North and South is transnational political activism that seeks to transform imbalanced power relations for social change, primarily for the benefit of others. One framing principle is todo para todos, nada para nosotros (for everyone, everything; for us, nothing). Solidarity between the North and South recognizes distorted power dynamics in the North and histories of oppression in the South and among marginalized communities in the North, and connects common struggles to have a greater effect. Through mutual aid, solidarity, engagement, and support, this transnational solidarity can act across borders to bring attention to and confront human rights abuses at the nation-state level. Both solidarity movements tend to be based on non-hierarchical, democratic principles.

In a demonstration of both types of solidarity at the 21st International AIDS Conference in Durban, more than 150 South-African and Indian activists and comrades from the North marched to the Indian consulate to deliver a petition letter. South Africa has one of the highest HIV burdens in the world and relies on Indian generics for the majority of its ARVs. The Indian government has recently faced external pressure because its patent laws take advantage of flexibilities that enable generic manufacturing. The Lawyers Collective fights for this enabling environment and for the preservation of civil society space. This year, the Indian NGO has been suspended from receiving international funding, which potentially undermines its work. Without strong advocacy for generic access, developing countries’ current ARV and future HCV direct-acting antivirals supplies are in jeopardy.

This action demonstrated good practices for North-South solidarity. Activists from the global North followed the collective leadership style, listened to organizers from the South, recognized their privilege, acknowledged critiques of their own governments, and worked to not impose their own agendas. They offered legal aid and funding, helped occupy the media center, and urged media coverage in the North.

Through practices of conscientious solidarity, activists can ground their advocacy in broader concerns of power imbalances and social inequalities to challenge the commodification of the cure, oppose drug monopolies, and demand legal flexibilities to liberate generics. Treatment activists can and must demand changes to the rules to make direct acting antivirals (DAAs) affordable for everyone who needs it.•