By Khairunisa Suleiman, Technical Co-Lead, Global TB CAB and Suraj Madoori, U.S. and Global Health Policy Director, TAG

On Sept. 26, 2018, the world came together at the United Nations General Assembly in New York for the first-ever High-Level Meeting on Tuberculosis (TB HLM), bringing hope for new political will and resources to jump-start the global response to the world’s leading infectious killer. But a draft declaration on TB had been finalized less than two weeks earlier, and the negotiation process had been prolonged and contentious. The fight had brought the global TB community to the brink, with the players nearly going into the TB HLM without a political framework that countries could agree upon. The delay was due to a narrow but deep deadlock between the U.S. government and the government of South Africa: The countries disagreed on paragraphs that supported the rightful use of TRIPS (the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property) flexibilities by governments to promote affordable access to new tools and treatments in the fight against TB.

The negotiations on the declaration provide an ideal backdrop to examine the realities and challenges around global political will to end the world’s leading infectious killer, spotlighting the main dynamic and contenders: the obstructionism of the United States government and the bold maneuvering by South Africa in expanding access to lifesaving medicines. As activists take forward the commitments beyond the TB HLM to expand access to medicines for TB, we are well advised to learn lessons from the history and political dynamics that fueled the negotiations.

The U.S. Threat at Every Step

At nearly every step of the negotiations, the U.S. government threatened to nix the TB HLM declaration if language on access to affordable medicines was retained, and U.S. negotiators repeatedly deleted the operative text. These moves frustrated South Africa, which is heavily burdened by TB, and other G77 nations that struggle in expanding treatment and associated tools. In solidarity with the global TB community, U.S. civil society organizations advocating on TB and access to medicines (A2M) sent a letter to their own government appealing for them to “work in good faith to find a political solution” in respecting other nation’s rights in exercising TRIPS flexibilities.1 The letter went unanswered.

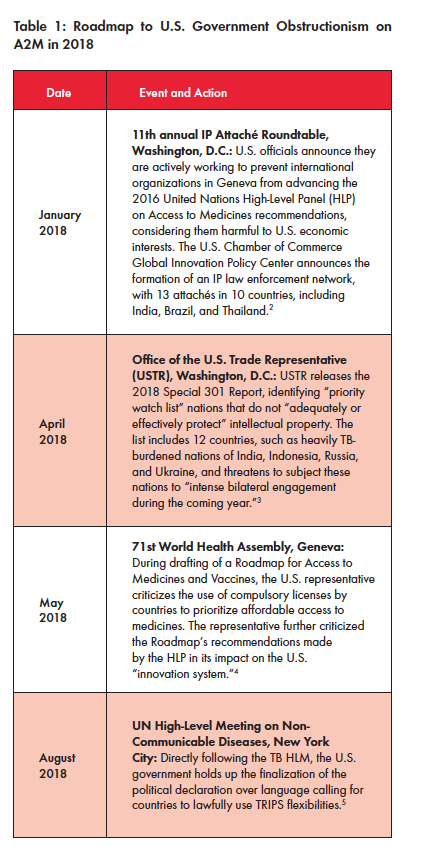

Yet, many A2M advocates contend that the disruptive involvement and hard-line stance of the U.S. government in these multilateral negotiations is neither new nor surprising. In fact, the protracted proceedings are part of a larger pattern in which the U.S. prioritizes industry profits over matters of public health. In just the past year, the U.S. government has penetrated multiple policy environments, aiming to rebuke other governments for trying to address their own public health crises (see Table 1). For example, in remarks to the 71st World Health Assembly in May 2018, U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said, “President Trump has made reducing the cost of prescription medications for Americans a top priority, and we have already begun taking action to improve affordability within our market-based, innovation-friendly system.” Azar further condemned nations for “practices by which other countries command unfairly low prices [for] innovative drugs.”

A Deceitful Ideology

The persistence of the U.S. government in narrowly focusing on the access provisions in the TB HLM, risking the whole negotiating process rather than encouraging other nations to end the world’s deadliest infectious disease with every tool possible, is consonant with the administration’s industry-centric “blueprint” on drug pricing.

While this harmful rhetoric and practice predates Trump, this strategy is laid bare in his administration’s May 2018 plan on drug pricing, called American Patients First: The Trump Administration Blueprint to Lower Drug Prices and Reduce Out-of-Pocket Costs. The largely industry-backed plan contains a strong mandate to the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) to go after other countries for the “global freeloading” on American taxpayers, ostensibly because other countries often pay substantially lower prices for drugs for which there have been U.S. investments in research and development (R&D).

The blueprint postulates that by going after other countries, i.e., reinforcing intellectual property (IP) rights and discouraging compulsory licensing, drug prices will somehow become lower in the U.S.. This truly deceitful ideology underpinned the U.S.’s objectives and engagement in the TB HLM.

TAG and many other organizations submitted public comment on the blueprint noting that such reinforcement of IP is no different from what the U.S. has done in the past, arguing that it is mere spin for demonstrating political will to a polarized electorate by an administration desperately seeking a win on drug pricing.6

This U.S. myopia also means that domestic patients with TB lose out, with the U.S. neglecting to address its own national pricing and policy issues at the TB HLM. The TB drug supply is often prone to disruptive stock-outs and vulnerable to fragile market conditions and unexpected price spikes, even in the U.S. In early 2018, manufacturer Sandoz unexpectedly discontinued the U.S. production of isoniazid, a key drug in the treatment of TB. Bedaquiline, one of only two new TB treatments that are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, continues to experience difficulty in uptake because of high costs in the U.S.—mirroring the issue of exorbitant pricing and limited access to the drug among low-income countries heavily burdened by TB.

South Africa Remains Valiant

Comparatively, South Africa’s approach to the TB HLM declaration was diametrically different to the U.S. When the draft declaration went public on July 20, 2018, South Africa broke a procedural silence on negotiations and valiantly advocated in favor of the stronger initial draft language on access to medicines.

The nation urged co-facilitators Antigua and Japan to consider including language for countries to exercise TRIPS flexibilities for affordable and accessible medicines and diagnostics. South Africa also advocated for delinking the price of medicines from the cost of R&D in order to increase affordability of TB tools. The next day, the G77 bloc of countries supported South Africa’s stance, thereby reopening negotiations on the TB declaration.

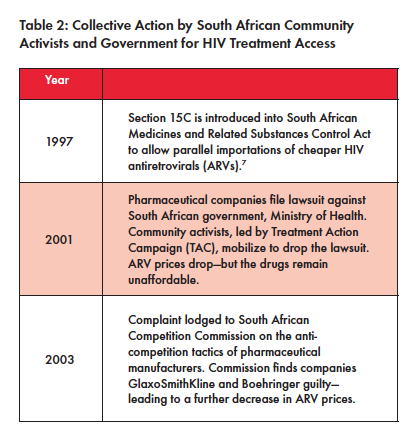

But South Africa’s valiant efforts are rooted in its political history. In the past, the South African government has weathered repeated attempts from lobbyists aligned with the USTR and pharmaceutical industry in its work to expand access to critical medicines for its residents through a combination of community activism and progressive policy (see Table 2).

Notably in 1997, South Africa passed the Medicines and Related Substances Control Act to allow for the importation of cheap antiretrovirals (ARVs) to treat HIV. In response, the U.S. continued to pressure South Africa to repeal or change the Medicines and Related Substances Control Act. Because of media attention, resulting from strong community activism, the U.S. relented and stopped pressuring South Africa in 1999.

This valor was on full display in the lead-up to the TB HLM. For example, South Africa government negotiated with pharmaceutical giant Johnson & Johnson to reduce the price of bedaquiline to US$400 for the six-month treatment course, a change that would benefit all countries that procure treatment from the Global Drug Facility. Civil society activism also contributed to this price decrease, threatening compulsory licensing and calling for a price of US$32 per month before the negotiations were finalized.8 Additionally, ahead of the new World Health Organization (WHO) drug-resistant TB (DR- TB) treatment guidelines, South Africa took another significant step by changing its national DR-TB treatment guidelines to include bedaquiline and prohibit the use of the toxic second- line injectables. This display of political will, alongside strong community activism, subsequently spurred the WHO to recommend the use of bedaquiline and prohibit the use of kanamycin and capreomycin in the treatment of DR-TB.

Political Will Beyond Paper Agreements

But ironically, even with this long history of political will and proactive steps to reduce drug prices, South Africa has never issued a compulsory license to challenge the IP for any drug, perhaps in fear of U.S. reprisal.

For example, the repurposed drug linezolid that is now used for TB is still patented and had only one distributor in the country until 2015.9,10 And it is still unaffordable for South Africa at US$ 442 per six month-treatment course.11 Activists contend that it would be life-saving for South Africa to issue a compulsory license for linezolid and import the generic version, especially now that the drug is part of the core regimen in the new WHO DR-TB recommendations.

In conversations with TAGline, activist Marcus Low of South Africa’s Treatment Action Campaign points to the dissonance in South Africa’s fight for policies to expand access and the government’s failure to take the critical step in implementation, particularly for underserved people in areas of the country hit hardest by DR-TB:

That is why I get upset when people say that TRIPS flexibilities are not needed in TB. People with XDR-TB in Khayelitsha who needed linezolid to have a chance at life could not access it for a long time due to the drug’s excessively high price, an excessively high price made possible through patent protection. The reason we have TRIPS flexibilities in international law is precisely to help us intervene in such situations.

The Real Work is Only Beginning

TB advocates should expect the U.S. to remain active in spurning any attempt to expand access to TB medicines well after the TB HLM. Azar doubled down on the U.S. government’s position to protect IP in his remarks at the TB HLM on Sept. 26, saying:

But we will not be able to conquer this challenge without new tools. Because we strongly support the development of these new tools, we cannot cede ground on intellectual property rights. (emphasis added)

Respect for intellectual property rights is not just an important international legal obligation, but also the very foundation of the innovation economy that we need to fight TB and other deadly diseases.

Unless we are satisfied with today’s treatments for TB— and how could we be—we must be vigilant in avoiding any measures that will discourage market actors from developing the therapies of tomorrow.12

The TB HLM declaration process reveals how far major international actors will go in the highly contentious policy space of access to medicines. Ultimately, thanks to South Africa’s bold resistance, language on access to medicines and TRIPS flexibilities was retained in the final political declaration—a significant win for the global TB community.

But the TB HLM political declaration represents only a single win in the battle with the USTR and U.S. government writ large, on access to medicines for TB. The recent U.S. political dynamic foreshadows the need for strategic, long-term, community-led activism in truly expanding access to medicines in TB.

Now, for TB activists and advocates the real work is only beginning: We must come together to catalyze and sustain the political will to move beyond paper agreements like the TB HLM declaration, pushing governments to use the TRIPS flexibilities to address their own epidemics. But the negotiations between the U.S. and South Africa also revealed stark disagreements among TB advocates on the value of TRIPS for a disease that sees very little innovation and investment in the first place. But it’s a fallacy that we can go without provisions to safeguard public health for future TB drugs, vaccines, and diagnostic tools. This is a strategic opportunity for the TB community to work with the A2M activists who have forged political will on these issues for years, rethinking the way we traditionally fund R&D in favor of alternative models that prioritize access from the beginning of drug and regimen development.

The U.S. is a critical donor nation in global TB efforts, both in programs and in R&D, forcing many countries to stay silent and concede to the USTR in fear of biting the hand that feeds them. Strengthening our community’s understanding about TRIPS flexibilities and access to medicines will enable us to bolster efforts to advance local advocacy, further building the political will necessary to embolden nations to use TRIPS flexibilities, and to better prepare countries to take on U.S. pressure.

TB activists and advocates must remain vigilant, vocal, and proactive. Marcus Low calls on the community, telling TAGline, “In the TB community there are some who think that we shouldn’t criticize J&J or Otsuka about unacceptably high prices because that will make them leave the TB field. But companies don’t do R&D in TB because we are being nice to them—there are much stronger market forces at play. There is a naiveté in the TB community about industry. We’ve played nicely, but companies like Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Gilead have

abandoned TB anyway.”

Under the Trump administration blueprint (and perhaps especially as we head into critical election years), the USTR has made it clear that it will continue to obstruct countries that exercise internationally recognized rights in multiple international policy platforms, many of which will inevitably include TB. TB advocates must be prepared to work with A2M activists to take on the USTR by methodically dismantling the “foreign freeloading” rhetoric, as well as engaging and monitoring future convenings of the World Health Assembly and large trade negotiations. In doing so, we must replace the “innovation” narrative that centers on protecting IP with R&D proposals that catalyze the next generation of tools for TB and prioritize affordable access for the people.

With the TB HLM declaration win as a green light, TB advocates must now hold the South African government accountable to take the critical next step in fully exercising its right to enhance access to affordable TB medicines. The political will must go beyond the HLM; the South African government should also influence other G77 nations to use TRIPS flexibilities and invest in R&D models that prioritize access to TB medicines for their residents. Lastly, country governments must work with community TB activists, already mobilized after the TB HLM, to make Pharma realize and amend its bad behavior. Community activists should further work with governments to explore policy options such as compulsory licenses for TB drugs, vaccines, and diagnostics to secure affordable diagnosis and treatment for their people. Only then will the fight during the TB HLM have been worth it for communities affected by TB.

ENDNOTES

1. Treatment Action Group. Letter to Nikki Haley, U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, on access to medicines and the TB High-Level Meeting. 2018 August. https://www.treatmentactiongroup.org/sites/default/files/letter_to_amb_haley_tb_hlm_med_access.pdf

2. New, William. US Working To Block UN High-Level Panel On Access To Medicines Ideas In Geneva And Capitals. Intellectual Property Watch. 2018 January. http://www.ip-watch.org/2018/01/22/us-workingblock-un-high-level-panel-access-medicines-ideas-geneva-capitals/

3. USTR Releases 2018 Special 301 Report on Intellectual Property Rights. Office of the U.S. Trade Representative. 2018 April. https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/press-releases/2018/april/ustrreleases-2018-special-301-report

4. Saez, Catherine. WHA Agrees On Drafting Of Roadmap For Access To Medicines And Vaccines; US Blasts Compulsory Licences. Intellectual Property Watch. 2018 May. http://www.ip-watch.org/2018/05/24/wha-agrees-drafting-roadmap-access-medicines-vaccines-us-blastscompulsory-licences/

5. NCD Alliance. Countdown to the HLM on NCDs: Advocacy Alert! 2018 August. https://ncdalliance.org/news-events/news/countdown-tohlm-on-ncds-advocacy-alert

6. Treatment Action Group. White House and Congress Must Boldly Address Drug Pricing and Ensure Access to Critical HIV, HCV, and TB Medications. 2018 July. https://www.treatmentactiongroup.org/sites/default/files/RIN_0991-ZA49_TAG_HIVMA_NASTAD.pdf

7. Fisher, William; Rigamonti, Cyrill. The South Africa AIDS Controversy A Case Study in Patent Law and Policy. The Law and Business of Patents. 2005 February. https://cyber.harvard.edu/people/tfisher/South%20Africa.pdf

8. Treatment Action Group. Activists call on Johnson & Johnson to drop the price of bedaquiline. 2018 July. https://www.treatmentactiongroup.org/sites/default/files/bedaquiline_pricing_statement_final.pdf

9. Médecins Sans Frontières Access Campaign. Linezolid Fact Sheet. 30 June 2014. https://msfaccess.org/linezolid-fact-sheet

10. Email communication with Dr. Ndjeka- DR-TB/ HIV director at National Department of Health, South Africa on 12 November 2018

11. TB Info. Urgent need to make linezolid available in South Africa at affordable price. 2016 January. http://www.tbonline.info/posts/2016/1/8/urgent-need-make-linezolid-available-south-africa-/

12. Department of Health and Human Services (U.S.). U.S. Government Statement at the U.N. High Level Meeting on Tuberculosis https://www.hhs.gov/about/leadership/secretary/speeches/2018-speeches/index.html