By Annette Gaudino, HCV/HIV Project Co-Director, TAG

Do you remember how old you were when you stopped believing in the monster under your bed? How many times did you have to look and see nothing there before you finally believed the danger wasn’t real? In the United States, the fear that price controls would irrevocably harm the prescription drug development pipeline is used to frighten Americans away from systemic change. But once you look under the bed—at the assumptions underlying that belief, up against real-world evidence—there is no rational basis for this fear, and the threat of the boogeyman can be put to rest. Here’s why:

Price Controls Already Exist in the Real World

The specter of price control is framed by the pharmaceutical lobby as an artificial interference in the otherwise natural and smooth functioning of markets. But the power to say no, to walk away from a negotiation, is the most rudimentary form of price control, and it is built into any true market. If we determine that something just isn’t worth the asking price, we can walk away. Of course, this is nonsense to anyone who depends on an essential medicine for their very life. Negotiating for your life is a hostage situation, not a free market.

Setting aside the terms of the debate, direct price controls on essential medicines exist in the real world, specifically in all high-income countries, with one exception: The U.S. is the outlier in letting manufacturers set prices, virtually without constraint. The industry campaign to demonize price controls is designed to keep the U.S. an outlier and to block any attempts to grant negotiating power to public payers such as Medicare. The Department of Health and Human Services’ drug pricing blueprint, American Patients First,1 frames the issue exactly as any pharmaceutical industry lobbyist would: “Every time one country demands a lower price, it leads to a lower reference price used by other countries.”

In other words, a threat to profits anywhere is a threat to profits everywhere.

But what do price controls actually look like in other countries? Germany provides a fascinating example for the U.S. Similar to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) before the individual mandate penalty was repealed Germans are required to buy health insurance (with 80 percent of Germans choosing the public national health insurance plan), and premiums are subsidized for those with low incomes. And as in the marketplace plans created under the current form of the ACA, coverage for a package of essential benefits is required, with no denials based on pre-existing conditions. Insurance firms compete on customer service, add-on coverage, and to some extent, price. But unlike in the U.S., healthcare plans in Germany are not-for-profit, and their executives have no fiduciary responsibility to deliver returns to investors.

The German system allows pharmaceutical manufacturers to sell any approved product at any price for up to two years— without coverage under the national plan. During this period, data on clinical efficacy in the real world is collected and analyzed in comparison with treatments already covered under the national insurance system. At the end of the period, the government offers the manufacturer a price for purchase and coverage by the public system, informed by comparative data and the price of existing treatments for the same condition. The German approach thus solves three real problems: It incentivizes medicine development through both quick return on investment and a guaranteed revenue for truly effective treatments; it generates real-world comparative data to inform clinical decision-making; and it provides distinct, data-based constraints on total health spending.

The Big Lie: Big Pharma Isn’t Making Enough Money

Fear of the price-control boogeyman rests on the belief that corporate profits are necessary to fund essential medical and scientific innovation. If unfettered corporate profits are necessary for lifesaving medicines, then why not argue that current profits are too low? Once again, American Patients First does just that:

The loss of patent exclusivity on successful products, new ACA taxes, and requirements to extend higher rebates and discounts to a markedly increased Medicaid and 340B population created an estimated $200 billion of downward pressure on pharmaceutical industry revenues [emphasis added]—during a five-year period when innovation was decreasing. International price controls and delayed global product launches exacerbated the problem.

This unsourced claim is easily refuted: Profit margins in the pharmaceutical industry dwarf all other sectors.

According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office,2 the 25 largest pharmaceutical companies have profit margins of 15%–20%, compared with 4%–9% for the global top 500 companies in other industries, with pharmaceutical sector revenues increasing $241 billion from 2006 to 2015. Sales revenues for a single company (Gilead Sciences) for a single drug class (direct acting antivirals—or DAAs—for hepatitis C) were $57 billion over the past five years. Total worldwide revenues for all DAAs since 2014 are estimated at over $66 billion, which has bought us treatment for only 5 percent of the estimated 71 million people living with chronic hepatitis C worldwide.3

In 2015, a U.S. Senate Finance Committee investigationon pharmaceutical pricing practices revealed an internal Gilead email discussion on the company’s recently acquired DAA sofosbuvir (brand name Sovaldi) in which Gilead executives discussed setting the launch price to establish a new benchmark for this class of treatments (and therefore future products) with no link to already incurred development expenses. These executives demonstrated what access to medicines activists had argued all along: There is little to no link between essential medicine drug pricing and the cost of their actual development and manufacturing.

Demand Drives Development

Demand, as defined by commitment from purchasers to generate revenue sufficient to justify the initial investment, is the true driver of invention, innovation, and access. This is seen most clearly with generic manufacturers: The market must be big enough to generate profit from the investment required to retool manufacturing equipment, purchase active pharmaceutical ingredients, and create a supply chain.

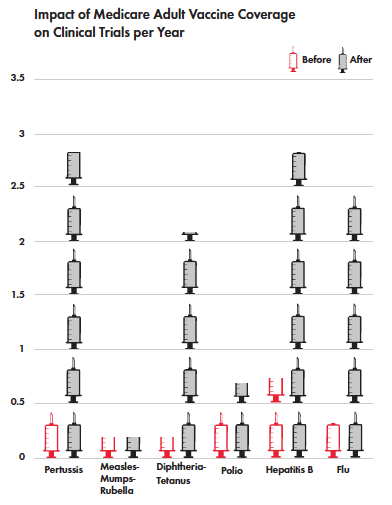

But it can also be seen in the development of new agents. A recent study by Amy Finkelstein, an MIT economist, found an increase in clinical trials for new vaccines in the U.S. after Medicare committed to paying for vaccination, guaranteeing a return on investment for approved vaccines. This shift included a 2.5-fold increase in clinical trials for new flu vaccines since Medicare extended coverage to vaccines in 2005.

But it can also be seen in the development of new agents. A recent study by Amy Finkelstein, an MIT economist, found an increase in clinical trials for new vaccines in the U.S. after Medicare committed to paying for vaccination, guaranteeing a return on investment for approved vaccines. This shift included a 2.5-fold increase in clinical trials for new flu vaccines since Medicare extended coverage to vaccines in 2005.

Fake Problems, Fake Solutions

Solutions to problems that don’t exist aren’t solutions. The debate over U.S. prescription drug pricing policy is constrained by the false belief that direct price controls would threaten the supply of new, effective medicines. This belief rests on the false claim that low revenue is a problem; therefore, only a system that maximizes revenue throughout the supply chain can deliver the essential medicines we need.

In addition to solving the affordability problem that restricts treatment access, we should be working to solve other real problems in medicine development. These include the lack of competitive clinical effectiveness research—head-to-head clinical trials that compare new medicines to existing treatments—and the need to invest in treatment for diseases that affect poor people and poor countries, rather than “me too” medicines chasing proven lucrative markets.

Looking under the bed and seeing there’s no monster there allows us to seek bold solutions for pharmaceutical development, rather than being held hostage by the industry’s legally sanctioned greed and fear-mongering.

Endnotes

1. Department of Health and Human Services (U.S.). American Patients First: the Trump administration’s blueprint to lower drug prices and reduce out-of-pocket costs. 2018 May. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/AmericanPatientsFirst.pdf

2. Government Accountability Office (U.S.). Drug Industry: profits, research and development spending, and merger and acquisition deals. 2017 Nov 17. https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-18-40

3. Global Hepatitis Report, 2017. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. http://www.who.int/news-room/detail/31-10-2017-close-to-3-million-people-access-hepatitis-c-cure