TAG’s executive director Mark Harrington spoke at the U.S. Senate briefing held on March 28, 2019, not long after World TB Day. He invoked the stories of leaders that had tuberculosis, such as Eleanor Roosevelt and Nelson Mandela, on the need to advance TB research and development through political will.

View/download the slides Mark presented

David Bryden: Our next speaker is Mark Harrington, who is the executive director of an activist think tank known as Treatment Action Group. Mark joined the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power in 1988 and went on with other AIDS activists to start the Treatment Action Group in 1992 and has played a leading role, not only on HIV/AIDS but on TB and on other issues as well. Mark is a writer and thinker. We’re really glad to have him here.

Mark Harrington: Thanks, David. Thank you to all the speakers, and thank you to the Senate staffers who are present. It’s really important that you’re here and you recognize the importance of the American contribution to the global and the domestic struggle against TB. There’s a little background that I want you guys to know about. TB, along with probably the plague, and influenza, is the biggest infectious killer in history. It’s estimated by Nature magazine that TB has killed one billion people over the last hundred years. TB was the cause of 20 percent of urban deaths in Western European and U.S. cities in the 19th century. So if you look through back all our family trees, many, many of those branches were pruned because people died prematurely of a disease that has been curable and preventable since before I was born in 1959. The fight against TB was one of the greatest public health victories of the 20th century, and then it became one of the greatest public health defeats in the later part of the 20th century, when all the innovation that led to BCG vaccination, that led to TB diagnosis, that led to a four-drug, six-month cure, all fell away after 40 years of underinvestment under the tide of HIV infection and of multi-drug resistant TB because of poor health systems and dis-investment by governments in the health of the poor in R&D.

As a person who’s been living with HIV since 1985, I’m alive because of the investments the American people have been making in biomedical research and particularly HIV research over the last 40 years. I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for that investment by the U.S. people. And yet, as a person living with HIV, even though I’m on a successfully developed treatment, my risk of acquiring TB is twenty-threefold higher than it is for somebody who’s not living with HIV, even though my immune system essentially looks normal. So I have to take that test we were asked about earlier every year, by my doctor, and I like getting it because it’s an old-fashioned skin test. And it proves even though I’ve been doing AIDS work all around the world for the last 30 years that I still haven’t gotten infected by TB, and I hope that will be the case as I continue to do our important work.

A lot of people know about the romantic 19th century Western European artists and pianists, and others who have died of TB, but many people do not remember or never knew that Eleanor Roosevelt, America’s pioneering First Lady and one of the key figures in the adoption of the Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, died of drug-resistant TB in the early 1960s. Nelson Mandela developed tuberculosis when he was a prisoner on Robben Island in South Africa, and yet he was cured. And I’ll never forget Nelson Mandela standing at the AIDS conference in 2004 in Bangkok and telling us that we will never defeat AIDS unless we also defeat TB. A quarter of the deaths from TB around the world are caused in people living with HIV, even though only 1 in 10 cases occurs in those people. And so those two diseases are inextricably entwined. And as we think about and struggle against one, we need to think about and struggle against the other.

But now let me give you a little bit of hope as well. I talked about the greatest public health defeat of the second half of the 20th century. The last twenty years, thanks to a surge in investment by the U.S. and other funders, including the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, have brought us some of those new drugs, new diagnostics that can detect TB and drug-resistant TB in two hours with a DNA test, a test that can detect TB in people with advanced AIDS in twenty minutes, for only three dollars a test, and now, just last year, we had two breakthrough studies. For the first time in a hundred years, we have a new TB vaccine candidate, that has been shown to reduce the incidence of TB disease in people at risk of tuberculosis. And it’s going to cost us about 500 million to 1 billion dollars to bring those two vaccines all the way through the pipeline. At the current rates of investment, it’s gonna take much longer than it needs to get those new vaccines, the new drugs that Cheri was talking about and the new diagnostics out to the people that need them in time.

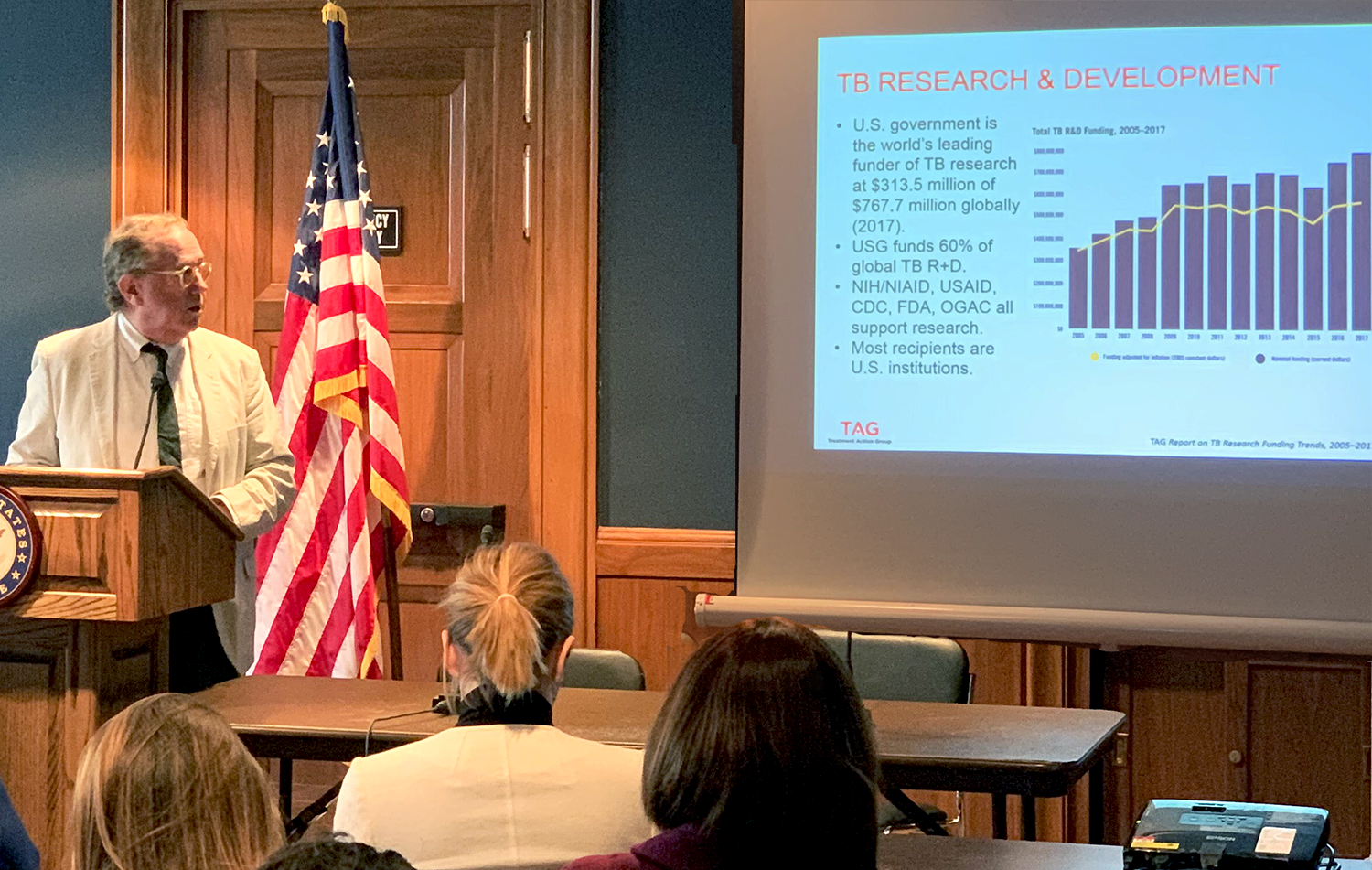

The U.S. government is the lead funder of TB research globally. There is a misprint on the slide. It’s actually: 66 percent of all funding globally comes from public sector around the world, and the U.S. funds about 40 percent of that – about $313 million. If you look at the yellow line, the purple line is showing how much TB R&D is over the last 14 years, but the yellow line shows you the numbers in constant dollars which show that we’re not really keeping up with inflation, and although last year was a record number, in real equalized dollars, it was about the same number as 2009. The NIH, AID, CDC, FDA and OGAC all play critical roles in TB R&D, along with our partners in the private sector and from other countries, but it’s important to notice that in TB, very few drug companies are in the space because they do not see a potential for earning profits. And so only 11 percent of the investment in TB R&D is from companies, and only four large major pharmaceuticals are in the space.

There’s a very new and important NIH/NIAID five-year strategic research plan for TB, which they released at the time of the UN High Level Meeting. I told you about some of the groundbreaking results on one of the two vaccines which was from GSK (it needs to go into Phase 3). The new TB drug, which has just been submitted to the FDA, is going to be reviewed and approved by August, it’s estimated, and the fact that we’re only about one-third of where we need to be in annual investment to reach the global goals against TB. So in the next slide, you can see the gap in TB funding between the Stop TB Partnership’s Global Plan to End TB and the actual amounts that we’ve been recording for the current period’s five-year funding targets. And you can see that the only area that’s fully funded is basic science (that’s largely thanks to the NIH), but diagnostics, drugs, vaccines do not receive anywhere near what they need, and then partly thanks to USAID and CDC we do have a significant amount of operational and pediatric research which is taking place and is closer to the target.

So how are we going to build the momentum to move forward, to reach the level of the targets that were set at the High-Level Meeting and Stop TB Partnership? We need to think about a “fair share” framework. Think about it as a Paris Accord for TB R&D, where there’s a metric you can use to apply to every single country, where they can voluntarily try to sign on, to reach a certain level of investment that would reach the global $2 billion a year that’s needed. So the U.S. investment is catalytic, the U.N. High-Level Meeting was also catalytic, and agreed to the $2 billion a year target that Stop TB had already put out. So our proposal, and we’ve been trying to get other agencies in the U.S., and other governments around the world to adopt, is that if every country devoted a tenth of one-percent of gross expenditures on R&D across the board into TB, we can close that gap.

And so, it may be hard to read here, but you can get our presentation later, and I also brought my card. Three countries have already met their fair share targets. South Africa is spending a whopping 183 percent of its target under the fair-share formula, and that’s largely because of the incredible partnerships the U.S. and South African researchers have forged in the last twenty years against both HIV and TB. But who would’ve guessed that little New Zealand is at 114% of its target, and the Philippines, which is certainly not a rich country, is at 161 percent of its target? So of the top twenty countries, three of them have already met this target. But the big ones, like the U.S., the U.K., Germany, Canada, India, South Africa, China and Russia, are not on that list and they should be. We should all be working to get the U.S. onto that list.

So how do we get there? It’s pretty easy. We need $131 million in new R&D investments from the United States. We need to bring that $313 million to $444 million. Using this formula, we’re going from 70 percent to 100 percent of what our target should be. We can split it across the agencies, as you see on the table, so that NIH/NIAID funding would go up to by about $86 million, AID funding would go up by 15 million, CDC by $8 million, et cetera. It would be a win-win, because it would help these agencies do their job better, it would help to grow U.S. leadership, which would motivate other countries to sign on board, and most importantly, it would help accelerate the development of those new interventions that you heard about earlier, where, for example, now, if somebody in South Africa is diagnosed with XDR-TB, in the old days, they would have a 70 percent to 90 percent chance of dying. Now, thanks to some of the new drugs, like bedaquiline, they have about a 70 percent to 90 percent chance of being cured, sometimes with only three drugs in only six months. This is a revolution in TB treatment for drug-resistant TB, the likes of which the world has been waiting since 1980. And it’s the first kind of real optimism in TB R&D since that golden age of antibiotic drug development starting in 1948 when streptomycin became the first drug that was active against TB.

So, we have a few more sort of real data here in these slides about how important different parts of the U.S. program are. One I’ll shout out is the CDC domestic TB Trials Consortium, which has contributed, over the last 40 years, some of the most amazing discoveries in TB research. The amount of funding it receives is absolutely pathetic – 10 million bucks a year and if you compare it to inflation, we’re down to the level we were at in the mid-90s during when the MDR-TB outbreak happened in New York. So, with our proposal, the CDC TB research budget would go up by about $9 million and that would enable them to double their investment in R&D and that would enable them to get into the space where they need to be about not only TB preventive drugs but TB prevention with TB vaccines. But that consortium found a really important new regimen that shortens prevention of TB from about a nine-month regimen to a twelve-week regimen where you take 24 pills – you take two pills once a week for twelve weeks, and then you don’t get TB.

One last thing that I’d like to mention is these breakthroughs have been paid for largely by taxpayers of the U.S. and other countries, and we need to bring the prices of those drugs and diagnostics down to levels where people can afford them. So, in line with the general trend of at least rhetoric about drug-pricing reductions, we need to actually achieve it in reality. Cheri talked about how global drug facilities have gotten the best prices for most of these TB drugs. Why can’t domestic TB programs in the U.S. access these global best prices? Guess who’s the biggest funder of the Global Drug Facility? It’s USAID. It’s U.S. taxpayers. We pay to develop the drugs, we pay the globe to get those drugs for cheap, and then the TB programs domestically can’t afford the drugs because the prices are too high. That’s crazy. We need to make global equity so that the innovations that Americans pay to develop are available to people that live in America just as they’re available to people who live in South Africa, India, and elsewhere.

So, I’m going to close there. I think it’s a time of great hope, but it’s also a time where there’s a need for catalytic and critical investment and there’s a need for political leadership by the kind of people you all work for and within this room.

Thank you very, very much.