The story of U.S. drug pricing run amok isn’t just about corporate arrogance and avarice—it is also about government permissiveness and inaction

By Tim Horn, Erica Lessem, and Kenyon Farrow

On December 1, 2015, the U.S. Senate Finance Committee issued a scathing investigative report concluding that Gilead Sciences strategically priced its curative hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatments Sovaldi and Harvoni to yield an immediate financial windfall for the company, ignoring evidence and expert opinion that doing so would bust the budgets of public and private insurers and, consequently, prevent the medications from becoming available to all who need them. In February, Valeant Pharmaceuticals Limited and Turing Pharmaceuticals stood before members of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, which conducted its own investigations into the sudden, inexplicable price increases for a number of lifesaving drugs. A month later, Turing executives were back on Capitol Hill, this time in front of irate members of the Senate Special Committee on Aging.

With the surge in narratives of scandalous corporate greed and villainy, the pharmaceutical industry’s drug pricing practices are now firmly entrenched in American political discourse. The real scandal, however, is that monopolistic drug pricing is completely legal in the United States. Political condemnation of the pharmaceutical industry for its fleecing of consumers can feel vindicating, but it is also specious and hypocritical in the face of long-standing governmental encouragement of profit-driven private-sector practices, even when they have very real consequences for public health. CEOs like Martin Shkreli of Turing know this and, indeed, fully and unapologetically inhabit this system.

Unless the recent public cries of outrage are addressed by stricter government regulations and the possibility of bona fide price controls, exploitive drug pricing practices can be expected to continue.

According to a 2015 IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics report, prescription drug expenditures in this country approached $374 billion in 2014. This represents a whopping 13.1% increase over 2013 spending that, according to the IMS report, can be at least partially blamed on one major factor: Sovaldi (sofosbuvir), Gilead’s premiere HCV regimen component that debuted in December 2013 at a wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) price of $1,000 a tablet ($84,000 for a 12-week course). Sovaldi alone accounted for one-fifth of this increase—an additional $7.9 billion in 2014 spending by insurers, entitlement programs, and individual patients. Sovaldi and Harvoni (a combination of sofosbuvir and ledipasvir) have actually been among the most costly prescription drugs to Medicaid programs. In New York State alone, Medicaid paid more than $360 million for Sovaldi in 2014 to treat approximately 4,000 of its nearly 60,000 recipients living with HCV.

And it’s not just HCV drugs that are straining budgets. WAC prices for antiretrovirals (ARVs) are also considerable. Genvoya (a combination of elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide), one of the recently approved single-tablet regimens for HIV manufactured by Gilead, debuted in November 2015 at $31,362 for a one-year course. It was welcomed as a bargain by groups like the Fair Pricing Coalition (FPC), if only because its launch price wasn’t higher than the 2015 WAC price for its predecessor, Stribild. And with the WAC prices of virtually all ARVs increasing between 6 and 8 percent a year—more than twice the rate of inflation—older regimens have effectively doubled their price since launch (e.g., Atripla entered the U.S. market in 2006 at $13,800 per year; it now exceeds $26,000).

WACs for many common generic drugs—which account for 80 percent of U.S. prescriptions and have saved the U.S. health care system $1.2 trillion between 2003 and 2012—have also spiked in recent years for a number of reasons, including industry mergers and acquisitions (and, quite possibly, collusion), that have reversed free-market competition trends necessary to keep prices low.

Equally troubling are companies acquiring the rights to historically low-cost (“undervalued” in corporate parlance) medications without marketplace competition and then raising the prices astronomically. Among the most rank examples: Rodelis Therapeutics, which purchased the rights to the 60-year-old tuberculosis (TB) drug cycloserine in August 2015, increased the price from $500 for 30 capsules to more than $10,000, but ultimately agreed to return the drug to its former nonprofit manufacturer; and Turing, which purchased the 50-year-old Daraprim (pyrimethamine) for the life-threatening parasitic disease toxoplasmosis, raised its price per tablet from $13.50 to $750.

The adverse effects of skyrocketing drug prices are well established—and becoming increasingly glaring. Most egregiously, the high cost of HCV drugs has resulted in a clear inability of people living with the virus to get curative treatment. Numerous U.S. health plans, both public and private, have instituted treatment utilization polices and prior authorization processes based almost entirely on cost-containment concerns. Many Medicaid programs cover HCV treatment only for patients with advanced fibrosis and have policies that deny curative therapy to people who use drugs or alcohol, despite U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) labeling, guidelines, and clinical evidence to the contrary.

The impact of high prices on patients for other drugs, including ARVs for HIV and medications for AIDS-related infections, is also considerable. Some private insurance plans, such as those offered by Ambetter Health in 12 states, have refused to cover the cost of several single-tablet regimens (in response to a joint advocacy campaign by the AIDS Foundation of Chicago and the AIDS Institute, Ambetter agreed in March to expand its list of covered options). Numerous private insurance plans also place ARVs in their highest-coverage tiers, which can mean steep co-payment and co-insurance amounts and cumbersome prior authorization requirements—not to mention higher premium costs eventually passed on to all policy holders.

Public payers such as Medicaid are also facing higher costs for newer stand-alone and co-formulated ARVs, resulting in efforts to give preferential coverage status to older regimen options (prior authorization requirements for all single-tablet regimens other than Atripla are now required by Illinois Medicaid). And when there’s a massive spike in a drug’s price, such as with pyrimethamine and cycloserine, payers balk, public resources are squandered investigating work-arounds and alternatives, and lifesaving therapy is delayed.

Exorbitant drug pricing, particularly when it impedes patient access, has long been a top issue for U.S. activists. In 1989, under intense pressure from ACT UP, Burroughs Wellcome reduced the price of the first approved HIV drug, AZT, by 20 percent, which, when combined with recommended dose reductions for safety reasons, resulted in a price drop from approximately $8,000 to $2,200 a year. A more recent example is the 57 percent domestic price drop for the TB drug rifapentine, which was finally announced by its manufacturer, Sanofi US, in December 2013 following a TAG-inclusive coalition effort demonstrating that its previous price, which vacillated wildly between $51 and $130 for a box of 32 tablets, was a barrier to treatment. Sanofi US lowered the price to $32 a box, $3 below the price requested by activists.

U.S. drug pricing and access activism continues in earnest. A central player since 1998 has been the FPC, of which TAG is a member. The FPC not only pushes back against HIV and HCV medication debut and annual (and sometimes twice-yearly) price increases that perpetually threaten financially constrained public-payer systems (e.g., Medicaid, Medicare, AIDS Drug Assistance Programs [ADAPs], the VA health system), but also works to ensure adequate support strategies for uninsured and underinsured individuals, such as patient assistance programs (PAPs), and to mitigate steep out-of-pocket costs, such as co-pay assistance programs (CAPs).

Unfortunately, the Burroughs Wellcome and Sanofi US examples are exceptions, and the net outcome of domestic pricing advocacy is a mixed bag. Some manufacturers heed a few advocacy demands, notably the need for discounted pricing for ADAPs and robust PAPs and CAPs, while sidestepping more fundamental changes promoted by activists such as ends to premium pricing and annual price increases. Others have willfully overlooked activist guidance and pushback—Gilead’s HCV treatments, for example, are still priced beyond what payers can reasonably bear without significant restrictions, along with PAP barriers for many people living with HCV unable to get curative treatment.

Regrettably, there is no evidence that the U.S. public’s frustration with drug pricing has brought much more than a bit of political theater and some public relations headaches for pharmaceutical executives. Cases in point: despite an unprecedented level of media attention and vilification in late 2015, the WAC prices of Sovaldi, Harvoni, and Daraprim remain at their outrageous highs. Thus, is it time for the U.S. government to consider prescription drugs as public goods subject to government regulations and price controls?

One possible intervention involves allowing Medicare—which accounted for nearly a third of prescription drug expenditures in 2014—to negotiate prices. Congress prohibited this possibility when it added the Part D drug benefit in 2003, leaving it up to the individual Part D private insurance plans to negotiate directly with pharmaceutical companies. Though these individual plans can refuse to cover some drugs for many diseases as a price-negotiation tactic, they must cover at least two products in each drug class and must cover all drugs for certain conditions, including HIV and mental illness.

Giving Medicare itself the power to bargain—which presidential candidates Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders, and Donald Trump are advocating—has bipartisan voter support, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation poll. There are a number of possible approaches for the president and Congress to consider, with a proposal supporting the secretary of Health and Human Services to negotiate high-cost prescription drugs included in the Obama administration’s FY 2017 budget. According to the Office of Management and Budget and the Congressional Budget Office, however, the potential cost savings associated with this proposal are likely negligible. What hasn’t been calculated are the cost savings that may come from bona fide centralization of price negotiations, with all drugs subject to coverage denials if unsubstantiated costs remain beyond what the public can reasonably bear.

Another strategy includes forcing manufacturers to divulge their research and development (R&D) costs along with their sales and marketing costs. Having access to this information could prove critical to payers, policy leaders, and activists in negotiating lower WAC prices and deeper discounts to insurers. According to an analysis conducted by GlobalData, many major prescription drug manufacturers spend more on marketing than on research. Additionally, manufacturers frequently cite massive R&D expenditures to justify their prices. A 2014 study conducted by the pharmaceutical industry–supported Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development indicated that it costs $2.56 billion to develop a new drug. However, according to a 2013 report by the Drugs for Neglected Disease initiative analyzing its own drug development practices, new drugs can be developed at a cost of less than $200 million—and that’s after taking into account the inherent risk of pipeline failures (see “Decoupling R&D and Egregious Pricing” ).

Another option to increase bargaining power that would work especially well for drugs for conditions that are rare in the United States (like TB and toxoplasmosis) is centralized procurement. In the absence of a system that can centralize purchases and negotiate volume-based pricing and discounts with manufacturers, medications in small markets are much more susceptible to price fluctuations and shortages and end up leaving capacity-stretched hospitals and regions to fend for themselves. Also challenging are strict confidentiality rules surrounding federal 340B drug discount determinations, which apply to many programs catering to low-income patients such as those living with HIV or TB, thereby preventing providers, payers, and community advocates from sharing information and ultimately working together to ensure that affordability thresholds aren’t being crossed (see “Differential Pricing” sidebar).

Shifting toward a national system that pools demand, at least for certain conditions, would not only help consolidate purchasing power, but also create a more predictable and streamlined market with less administrative and outreach work for manufacturers or suppliers. The current initiative to create a national emergency stockpile of some key TB medicines under President Obama’s National Action Plan for Combating Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis offers an entrée into creating a more stable, broader procurement system, which will be squandered without expansion of the mandate for centralized procurement of all TB drugs.

Also of considerable interest are “march-in” rights under the 1980 Bayh-Dole Act, whereby the National Institutes of Health (NIH) can break a drug’s patent(s) if federally funded research is critical to its development and “action is necessary to alleviate health and safety needs which are not being reasonably satisfied [or] available to the public on reasonable terms.” Lawmakers and activists have long argued that this readily applies to prohibitively priced drugs. Thirty-five years later, however, the NIH has never exercised its march-in rights, denying five petitions—including one earlier this decade challenging the intellectual property rights of the HIV protease inhibitor Norvir (ritonavir), the price of which was raised 400 percent in December 2003.

Other strategies that have been noted by candidates, elected officials, and advocates include:

- increasing federal involvement in state Medicaid program negotiations for supplemental rebates;

- reducing the Medicare Part B percentage-per-sales-price disbursement to providers for certain drugs and biologics administered in clinics or hospitals, thereby discouraging the use of high-cost products over cheaper, efficacious options;

- replacing industry-set monopolistic pricing with cash prizes for researchers and manufacturers developing new compounds with clear therapeutic value over existing agents, along with generic competition immediately after FDA approval;

- legalizing the importation of brand-name and generic drugs from countries with price controls—an option popular with the U.S. public—but facing considerable pushback from drug makers, the FDA, and insurers;

- speeding up FDA review and approval times for generic versions of essential off-patent drugs without competition;

- making it more difficult for manufacturers to block or delay generic drug competition (e.g., Turing’s ploy of maintaining Daraprim in a tightly controlled distribution system to prevent generics manufacturers from acquiring the amount of drug necessary to conduct bioequivalence studies);

- and, of serious concern to TAG and consumer protection groups, deregulating FDA approval processes to encourage lower-cost products by reducing stringent registrational requirements.

Many of the arguably pro–free market system approaches described here have, however, been introduced by federal and state policy makers, only to fizzle out or be voted down. With the growing public frustration with drug pricing practices, particular in an election year, the time is ripe for government action. And if these moderate proposals don’t work—that is, if they fail to reduce budget-busting expenditures while ensuring fair profits to drive ingenuity and R&D investments—bolder steps, with an eye toward price-control measures being employed to maximize affordability in other high-income countries (see figure below), will be necessary.

Special thanks to Sean Dickson, JD, MPH, of the National Alliance of State & Territorial AIDS Directors (NASTAD) for his review of this article.

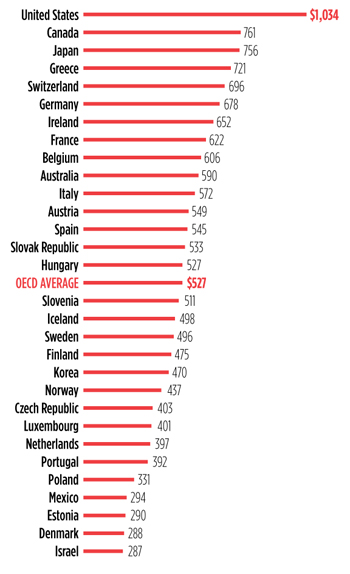

FIGURE: Price Controls in High-Income Countries

OECD member country expenditures on retail pharmaceuticals, per capita (US$), 2013 (or nearest year)

The disparity in drug prices between the United States and other high-income nations—listed in this bar graph of retail pharmaceutical expenditures are country members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)—certainly contributes to the growing public outrage at their prohibitive costs and the demand for more aggressive price controls. In fact, the United States is the only country in the OECD that does not impose price controls directly on the pharmaceutical industry.

Examples of price controls in other high-income countries include: maximum annual national budgets dedicated to drug expenditures; prescribing budgets and caps placed on health care providers and clinics; pharmaceutical company profit controls; price controls on specific drugs or within classes of drugs; setting prices based on comparisons with those in other countries; and economic evaluations.

The result? In the United States, the level of pharmaceutical spending was twice the 2013 OECD average and more than 25 percent higher than in Canada, the next highest spender. At the other end of the scale, Denmark spent less than half the OECD average.

Adapted from: OECD (2016), Pharmaceutical spending (indicator). doi: 10.1787/998febf6-en.

SIDEBAR: Decoupling R&D and Egregious Pricing—Does Innovation Suffer?

Protectors of the status quo defend exorbitant drug pricing by inciting fears that curbing the rising costs of pharmaceuticals will discourage innovation. But are affordable pricing and innovation really incompatible?

For many reasons, the answer is no. First, as estimates of research and development (R&D) costs are greatly inflated, the revenues needed to recoup R&D costs are much lower than commonly reported. Second, overpriced prescription drugs like Sovaldi and Harvoni have rapidly recouped far beyond even the highest estimated R&D costs. Older drugs like pyrimethamine and cycloserine have been on the market for decades—long enough to have recovered their costs many times over, with no additional research conducted in recent years to justify price increases. However, some opponents of drug cost controls argue that high prices allow for funding of future R&D, including the development of new products, rather than just recouping previous investments to bring existing products to market.

The pharmaceutical industry claims that its commitment to R&D of new and improved therapies is largely dependent on current sales of existing products; this is patently false. In the United States alone, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the Department of Defense, the Food and Drug Administration, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Agency for International Development, and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority all contribute vast amounts of public resources to help subsidize R&D that will ultimately translate into substantial shareholder dividends. U.S. government funding alone accounted for over a third of all spending on R&D for tuberculosis in 2014. The discovery of Gilead’s groundbreaking treatment for HCV, Sovaldi, was rooted in NIH- and VA-funded research, and its phase II clinical development was conducted, in part, by the NIH. And yet most people in this country who now need Sovaldi cannot benefit from it—due to its price, it remains largely out of reach.

But will efforts to curb rising drug costs deter innovation? Price controls, such as those in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) high-income countries, have been very effective at lowering drug spending (see figure, page 6). But several critiques, including a 2008 report from RAND Health and a 2004 study from the U.S. Department of Commerce International Trade Administration, caution that those savings come at a steep cost to R&D.

The RAND report posited that price controls would create modest consumer savings but risk larger costs through decreased innovation in the long run, even leading to decreased life expectancy. Instead of price controls, it favors reducing co-pays and other out-of-pocket expenditures that affect consumers.

The U.S. Department of Commerce International Trade Administration estimated diminished revenues in the range of $18 billion to $27 billion annually due to price controls in OECD countries and concluded that, without price controls, more money would be available for R&D.

But these analyses have serious weaknesses. First, while it is logical to think that reduced revenues resulting from price controls leave less money available for pharmaceutical companies to invest in R&D, it is unclear whether windfall profits from uncontrolled drug pricing are proportionally invested back into R&D. Second, both studies extrapolate data from a small set of OECD countries—just six in the case of the Department of Commerce report—to various markets including the United States, without considering the various factors that can influence prescription drug consumption and profit. In fact, the Department of Commerce report states that its analysis is based on two very flawed assumptions: that financial resources would be available to cover higher drug prices and that increased expenditures would not affect sales volumes. From the rationing seen with hepatitis C drugs, we already know this is not true. And the RAND analysis misses the point that if drugs are not affordable to public payers and private insurers, cost mitigation strategies for consumers, such as co-pay assistance programs, are insufficient to create adequate access.

To be sure, though, drug sales do indeed support investments in R&D, even if those are lower than what is often reported due to public support and exaggerated estimates of R&D expenditures. Also, importantly, anticipated drug sales play a large role in determining which products developers pursue, leaving out diseases that affect small numbers of people in this country.

Uncoupling the cost of R&D from sales would help with fair pricing. It would also encourage R&D regardless of how large or profitable a disease market may be. Several ideas for how to do this exist. For example, Médecins Sans Frontières and others have introduced the 3P Proposal to overhaul funding for TB R&D: Push funding to finance R&D activities up front (through grants); pull funding to encourage R&D activities through the promise of financial rewards such as “milestone prizes” on the achievement of certain R&D objectives; and pool data and intellectual property to ensure open collaborative research and fair licensing for competitive versions of the final products. As the United States continues to explore new options for curbing rising drug prices, it too should fully evaluate alternative systems for funding R&D.

With alternative research financing, more innovation could occur, without driving up prices. But even under the current R&D financing paradigm, the U.S. government can—indeed must—do considerably more to ensure fair drug pricing and access, without sacrificing innovation.

SIDEBAR: Differential Pricing of Outpatient Prescription Drugs in the United States

Pharmaceutical industry representatives frequently argue that wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) prices do not adequately represent the actual prices paid by private or public payers for their drug products. This is true: different payers, because of price adjustments made possible through negotiations, volume-based purchasing, prompt payments, and discounts and rebates required by law, typically end up paying different amounts for prescription drugs, and pharmaceutical companies bring in revenues based on a net price below the WAC.

But how much below the WAC, exactly? And how can we work to ensure that these pricing adjustments aren’t simply heralded as market-regulated price controls, but actually translate into affordable pricing for public payers, private insurers, and consumers? So many of the details pertaining to the costs of drugs—costs we cover in cash at the pharmacy, as taxpayers, and in the form of increasing private insurance plan deductibles—are shrouded in layers of secrecy. This makes it incredibly difficult for advocates to meaningfully engage with both manufacturers and payers—not to mention the array of health care and pharmacy systems shouldering some responsibility for the high costs of prescription drugs—to benchmark prices and ensure that cost does not stand in the way of access.

| Average wholesale price (AWP) | The wholesaler’s catalog or list price; approximately 120% of the WAC price. Public price |

| Wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) | The manufacturer’s negotiable list price to wholesalers. Public price |

| Average manufacturing price (AMP) | The average price paid to manufacturers by wholesalers for drugs sold to pharmacies. Confidential price reported to the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) by manufacturers |

| Best price (BP) | The lowest price paid by private payers to manufacturers for brand-name drugs, taking into account rebates, discounts, and other price adjustments. Confidential price calculated by CMS |

| Medicaid rebate | Federal unit rebate amount (URA) calculations are used to determine the rebates that must be offered to state Medicaid programs by manufacturers. URAs for brand-name drugs are either a minimum of 23.1% of the AMP or the difference between the AMP and the BP (whichever is larger), plus additional rebates if the AMP increases since the drug’s launch price exceeds the consumer price index-all urban consumers (CPI-U) marker of inflation. The URA for generic drugs is 13% of the AMP, without other mandatory adjustments. In addition to URAs, many state Medicaid programs negotiate supplemental rebates with manufacturers. Confidential price |

| 340B price | The 340B drug rebate program extends URAs to eligible health care organizations and covered entities, such as federally qualified health centers, Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program grantees, AIDS Drug Assistance Programs, and TB clinics in order to set a maximum, or “ceiling,” price for outpatient drugs. Participating organizations and entities are free to negotiate additional rebates that exceed the URA; they are also allowed to bill private payers at rates closer to the public list prices, with the difference between the acquisition cost and reimbursement amount to be reinvested in patient care and services. Confidential price |

| “Big Four” prices | The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the Department of Defense, Public Health Service/Indian Health Service, and the Coast Guard—the “Big Four”—receive special pricing discounts on prescription drugs. These drug prices are capped at no more than 76% of the non–federal average manufacturer price (non-FAMP)—a 24% discount from the net prices wholesalers pay to manufacturers for covered drugs. This is the federal ceiling price (non-FAMP x 0.76). The VA average price may be lower than the price available to the other Big Four because the VA negotiates further price reductions using its preferred formulary. Big Four prices may be 40% to 50% of the AWP and are made public: http://www.va.gov/nac/index.cfm?template=Search_Pharmaceutical_Catalog |