Slow Implementation for Needed Changes

After a century of failed efforts, decades of debate, and months of partisan rancor, this past March, Congress finally passed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 and Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act. The 2010 health care reform overhaul package is the most comprehensive national health care legislation in the history of the United States and the most ambitious expansion of health care since the creation of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965. While this historic law fell short of a public option with universal coverage that the HIV community, and most of those who believe that health care is a basic human right, called for, it will provide coverage for an estimated 32 million uninsured Americans when fully implemented after 2014.

The new law does not radically change HIV care at the outset. In some ways, people with HIV have had more flexible and comprehensive treatment options than many other Americans, at least since the passage of the Ryan White CARE Act in 1990 — despite frequent abuses of drug price increases by industry and equally outrageous and frequent interruptions of treatment manifested by egregious and cruel waiting lists at the state level — which at last count topped over 1,800 people — for antiretroviral treatment.

If the changes mandated in health care reform are implemented and given time to evolve, the U.S. health care system will undoubtedly improve, but these changes will not be achieved overnight and for people with chronic diseases or those who currently lack adequate health coverage, progress may seem agonizingly slow — nor will the law fix all the problems inherent in the fragmented U.S. health care landscape.

The speed and scope of implementation of health care reform depends on a labyrinthine system of interacting factors and players at the federal, state, and private sector levels, and will also depend on how adeptly the Obama administration can push through needed regulatory frameworks before needing to respond to the coming election cycles. Many people with HIV were unable to meet Medicaid’s stringent eligibility requirements — not only the low income threshold — but the requirement to be medically disabled.

Key Changes and Their Impact on HIV Treatment and Care

1. Impact on low-income people who use Ryan White clinics and the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP)

When the first anti-HIV drug, AZT (Retrovir, zidovudine), was approved in 1987, there was outrage because of its then unprecedented cost of $10,000 per year, much more than most people with AIDS could afford. Thus,a major reason behind the original push for the Ryan White CARE Act was the inadequacy of Medicaid, the nation’s primary healthcare program for people with low income.

Many people with HIV were unable to meet Medicaid’s stringent eligibility requirements — not only the low income threshold — but the requirement to be medically disabled.

NOW: The new law changes both of these enrollment barriers through the expansion of Medicaid coverage to low income individuals and families. As such, the annual income limit will be raised from $8,014 to $14,404 for an individual, but more significantly, people will no longer have to become disabled by disease to qualify.This also means much more comprehensive coverage, including hospitalization and a full drug formulary, than what Ryan White offers. Since the majority of people who rely on Ryan White-funded clinics and ADAP fall within the new income limit, this Medicaid expansion will stabilize and improve healthcare for most low income people with HIV who do not have private insurance. By 2014, when this component of the reform law is fully implemented, many people with HIV will no longer have to face the horror of ADAP waiting lists again. Ryan White and ADAP will finally become the programs they were meant to be — the emergency provider of last resort.

2. Impact on people who were denied coverage by private insurance

One of the basic concepts behind health insurance is the distribution of risk between the young and the old, the sick and the healthy. Many people with HIV who can afford to purchase private health insurance have been unable to do so due to the preexisting condition of their HIV infection.

NOW: This practice will be prohibited for private insurers under the new reform law starting in 2014. However as a stopgap measure between now and 2014 the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) will administer a temporary national high-risk insurance pool. To qualify, individuals must be uninsured for at least six months or must have been denied a policy because of a pre-existing condition. Out-of-pocket expenses will be capped for individuals at $5,950 per year. The combination of private insurance, state regulated insurance “exchanges” and federal mandates are supposed to provide near universal coverage by 2014, including a mandate for all U.S. citizens to purchase health insurance. The rationale of the state exchanges is to allow market forces to keep costs affordable while allowing people to choose the amount of coverage best suited to their needs. It is unclear how or even whether this will work in practice, as there is a danger that premiums will simply be too expensive. Federal subsidies will be provided for people making less than $43,320 a year, with possible exemptions for certain categories of people including those with yet undefined “financial hardships.” The difficult details of how this will actually work remain unclear.

3. Impact on people receiving Medicare who are stuck in the $3,600 Medicare drug coverage donut hole

For many people with Medicare drug coverage, the infamous “donut hole” created under the Part D expansion during the Bush Administration has caused immense frustration. To put it simply, people in the program pay the first $300 in prescription drug out-of-pocket expenses in addition to their monthly premiums. Plans then usually cover up to $2,830 per year in prescription drug costs at which point individuals must then fork over an additional $3,610 “donut hole” before they can take full advantage of the program.

NOW: Over the next ten years, Medicare Part D provisions will incrementally expand to eventually fill the donut hole. For people with HIV, starting in 2011, all brand name drugs (including most HIV medications) will be offered at a 50% discount, plus a $250 federal rebate will be paid directly to individuals this year. Currently, ADAP has been covering people stuck in the donut hole through a wrap-around measure, but since ADAP funds cannot be used to fill the hole, this means most people end up getting their medication through ADAP instead. Starting next year, ADAP can help fill the hole, and people will revert back to getting their medications through Medicare, paying just 5% of the drug cost, and freeing up much needed ADAP dollars for others without any drug coverage.

Looking Forward

Despite the stabilizing progress the 2010 health care reform law will make toward improving health care for people living with HIV, the future is certain to bring continued challenges in health care access, quality, and cost. Although many of the most important reforms do not go into effect until 2014, the protracted implementation will likely provide sufficient time for states to transition people from Ryan White-funded programs to newly created entities and structures. There are some glaring problems, such as the exclusion of undocumented immigrants from participation, the lack of cost control on drugs and insurance premiums, and the failure to address physician reimbursement to further stabilize the system. However, the health reform law is a giant leap forward. It will take much work on the part of people with HIV and their advocates to help ensure that the promise of health care reform is kept for people with HIV and everyone else in the United States.

For more information on health care reform, please visit the following websites:

- HealthReform.gov (Obama Administration website on new law)

- Treatment Access Expansion Project (Analysis of HIV-related provisions)

- Kaiser Family Foundation (Summaries and implementation timeline)

References

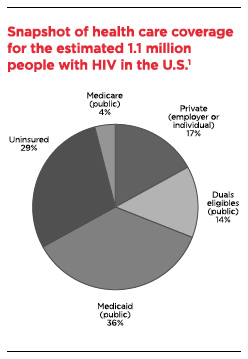

- Kaiser Family Foundation bassed on Fleishman JA et al., Hospital and outpatient health services utilization among HIV-infected adults in care 2000-2002. Medical Care, Vol 43 No 9, Supplement, September 2005; Fleishman JA, personal communication, July 2006.