By Lynette Mabote-Eyde and Mike Frick

Too often, major scientific advancements against tuberculosis (TB) get lost on the long and winding road of policy translation into practice. TB preventive treatment (TPT) has faced decades of dislocation between progressive global World Health Organization (WHO) guidance and lagging national-level guidelines and programmatic implementation. In some places, however, TPT programs are coming closer to matching recommended practice thanks to persistent advocacy by civil society and communities affected by TB. Speaking in a united voice, advocates have leveraged the components of the Availability, Accessibility, Acceptability and Quality (AAAQ) framework — a human rights standard for defining access under the rights to health and scientific progress — to strengthen national-level TPT responses by policymakers and HIV and TB programs within ministries of health.

This advocacy has brought about a tectonic shift in the visibility of newer, short-course TPT regimens called 3HP and 1HP that are based on the drug rifapentine. These regimens pair rifapentine with a second drug called isoniazid and can be completed in 12 weeks (3HP) or as little as 28 days (1HP). According to WHO data, 185,350 people in 52 countries were treated with rifapentine-containing TPT regimens in 2021, an increase from 25,657 people in 37 countries in 2020.1 This sizable jump did not result from the concerted effort of a single year, but rather the accumulation of many actions taken over the last five years. Using the shortest, best regimens based on rifapentine to prevent TB is key to realizing Sustainable Development Goal 3, which aspires “to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages,” including by ending the TB epidemic by 2030. This impressive recent progress demonstrates the importance of community-led TPT implementation and advocacy, and provides a roadmap for navigating the considerable distance left to travel before access to the best available standard of TB prevention becomes the norm rather than the exception.

Embracing Newer TPT Regimens to Save Lives

A recent modeling study published in Lancet Global Health found that by scaling-up short-course TPT to people living with HIV and TB contacts, governments can prevent 850,000 deaths through 2035; 700,000 of these averted deaths would be among children aged 15 years and younger.2 In particular, the study demonstrated that delivering short-course TPT regimens like 3HP via contact tracing — a process in which people exposed to TB through close contact with someone with the disease are screened for TB — could lead to a 13 percent reduction in the number of contacts who develop TB and a 35 percent reduction in deaths over the next 12 years. This evidence shows that short-course TB prevention is not a luxury but a matter of urgency for persons affected by TB, their household members, and other close contacts.

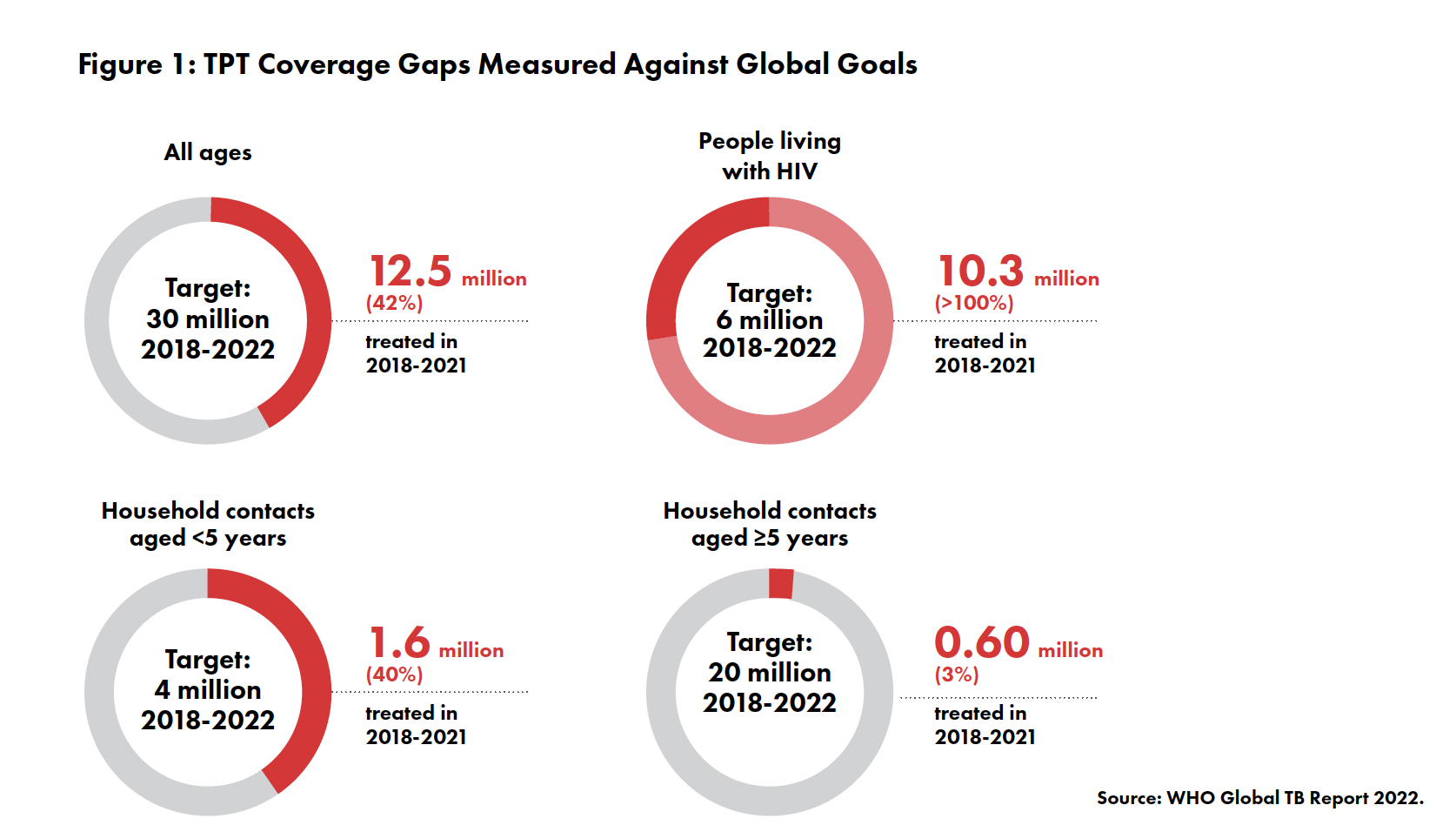

Yet too few people receive TPT: only 12.5 million out of a global target of 30 million people from 2018 to 2021. Most of these people were people living with HIV (PLHIV), meaning other groups at risk — including children and family members and other close contacts of people with TB — are still in need of protection (see Figure 1). Among those who did receive TPT in recent years, most were given versions of an older regimen called isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT), which must be taken daily for 6 to 36 months, instead of newer, shorter, and safer options like 3HP and 1HP.

Evidence that IPT can protect against TB has been available for more than six decades, yet the first global guidelines recommending TPT did not appear until after the turn of the twenty-first century.3 Initially, these guidelines focused on preventing TB among PLHIV. This was mostly due to the fact that TB is the leading cause of death for PLHIV, who are 20–30 times more likely to acquire TB than HIV-negative people.4 Even among PLHIV, uptake of TPT was dismal until 2016–2018 when there was a strong push to initiate people with HIV on IPT.

For PLHIV this was no easy ride. Many people complained about the high pill burden, little to no treatment literacy around IPT, and the lack of follow-up and psychosocial support. Many were reported to have either hidden or thrown away their IPT medicines. Others reported that due to reoccurring stock outs of vitamin B6 in their health care facilities, side-effects of IPT like peripheral neuropathy were unbearable. The reality was that IPT was “prescribed, but not taken as prescribed.” More had to be done — not only for people living with HIV, but also for those people who were not HIV positive but affected by TB, such as household or other close contacts, who remained on the margins of this evolving narrative.

Changing the TPT Narrative

The story started to change when scientific advances brought forward newer regimens to IPT that were shorter and more tolerable. Results from the PREVENT-TB study demonstrating the safety and efficacy of 3HP were published in 2011 and results from the BRIEF-TB trial of 1HP in 2019. The introduction of these two rifapentine-based regimens led to an overhaul of TPT. The combination of isoniazid with rifapentine was a game changer: people no longer have to take 6 to 12 to 36 months of daily treatment to prevent TB. As a result, affected communities (including those living with HIV) began to demand access to TPT as a tool to achieve their #RightToPreventTB and to protect their families from this deadly yet preventable disease.

But the narrative only really changes when countries adopt WHO guidance and translate that science into implementation. Country-level efforts continue to move at a snail’s pace. “The government may think that policies alone are enough. But, like a chain message, many surprising things are often encountered at the grassroots level. People must be aware and responsive of their right to health to demand their rights be fulfilled,” says Lusiana Aprilawati from the TB survivor organization PETA in Indonesia, explaining that community empowerment must accompany policy change.

It was through persistent advocacy by a growing movement of TB advocates, survivors, activist researchers, and responsive policymakers that the TPT story entered its next chapter. Attaching a human face to TB and promoting responsive, client-centered TB services was difficult. This advocacy required taking TB prevention out of the laboratories and into communities while pushing for decentralized care. These efforts found an initial footing within the more coordinated HIV movement, which had a long-standing commitment to patient-centered care as expressed through innovative models such as differentiated service delivery (DSD).

One of the most important interventions came in 2018 from the Unitaid-funded IMPAACT4TB project led by the Aurum Institute (TAG is a funded member of the consortium). The project worked in 12 countries to pilot studies, support early program experience, and expand access to rifapentine- based TPT. Project partners helped governments reform. their TPT guidelines to incorporate 3HP and are now doing the same for 1HP. The IMPAACT4TB project worked on all four dimensions of the AAAQ framework — effectively promoting human rights-based, client-centered TPT responses to galvanize a paradigm shift from long-course IPT to short- course 3HP and now 1HP.

Advocating for AAAQ

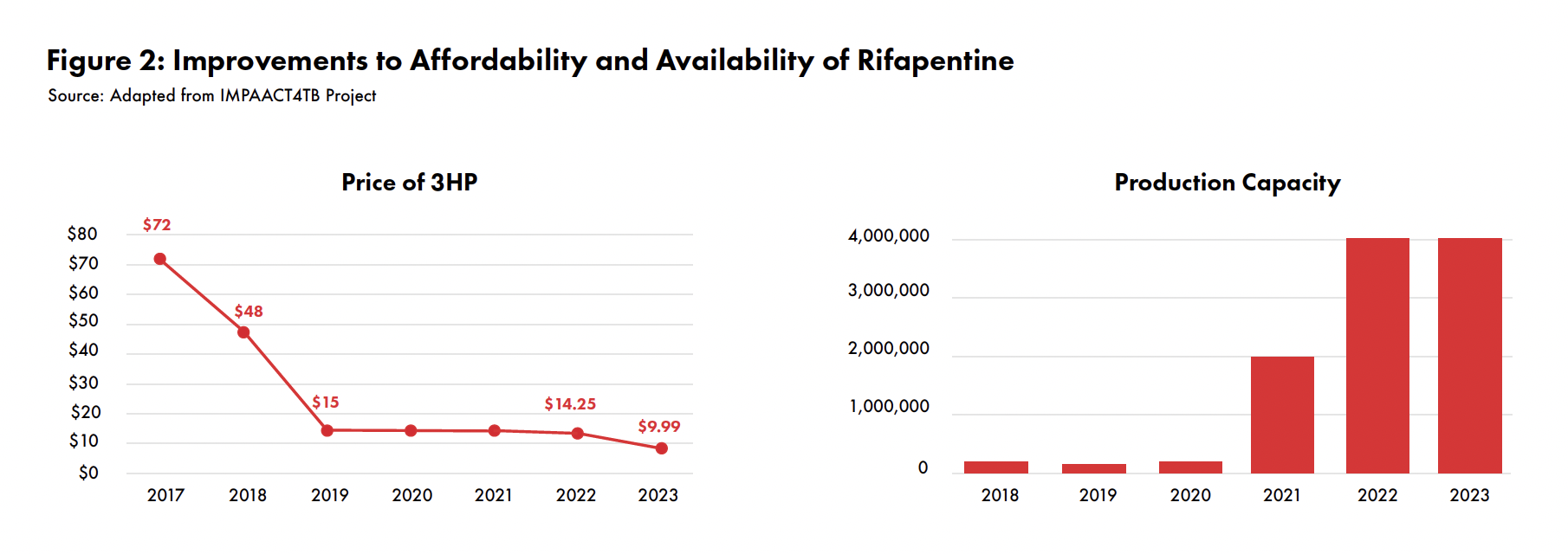

The IMPAACT4TB project increased the availability and ensured the quality of 3HP and 1HP by creating the conditions for two generic manufacturers to bring new formulations of rifapentine to the market and have them quality assured by the WHO and Global Fund. As a result, the global supply of 3HP increased dramatically: from 180,000 patient courses in 2018 to over 4 million in 2023. At the same time, the accessibility and affordability of 3HP improved with successive negotiations between suppliers and purchasers that reduced the price of 3HP from $72/patient course in 2017to$14.25 by the end of 2022 (seeFigure2). On the sidelines of the United Nations High-Level Meeting on TB in September 2023, the U.S. Government unveiled an even lower price of $9.99 per 3HP patient course from the manufacturer Lupin (a 30% price decrease).

While working on availability, accessibility, and quality, the IMPAACT4TB project did not forget about the fourth AAAQ plank: acceptability.

A hallmark of the project was its work with civil society and affected communities to undertake county-level policy advocacy and community demand creation. Acceptability concerns about the short-course TPT regimens are often lost in translating policy to practice. Countries are slow in developing TPT data collection systems, job aids, and training courses for health care workers to ensure that people prescribed TPT understand the importance of TB prevention for their households and other close contacts.

Civil society and affected communities have worked hard since 2019 to promote TPT treatment literacy as well as community-led monitoring. Leveraging a “training of trainers” treatment literacy strategy, an IMPAACT4TB community partner, the Coalition of Women Living with HIV (COWLHA) in Malawi, has reached 5,678 people by working with women expert clients in the last four years. At the policy level, their advocacy led to Malawi being the first country to recommend rifapentine-based regimens as the preferred option for populations for which the treatment was indicated. Short-course TPT regimens are included in the HIV Clinical Management Guidelines and name PLHIV, TB contacts, children under the age of five years old, and prisoners as priority populations. Financial support for national TPT scale-up was secured from development partners such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria as well as PEPFAR. COWLHA’s literacy sessions, focus-group discussions, and community campaigns have increased the number of people accessing TB screening services and asking for short-course TPT in health facilities. As of March 2023, these expert clients — who receive “refresher trainings” to keep their TPT knowledge up-to-date — have referred 466 household contacts for TB screening, and a total of 2,685 people from their support groups have accessed 3HP. COWLHA also worked with partners such as the Malawi TB CSO Network, the National TB and Leprosy Control program, and UNAIDS to develop a data collection tool to promote community-led monitoring (CLM). Data generated through CLM were used to lead national-level advocacy to improve the scalability of 3HP beyond their focal districts.

While creating the conditions for communities to accept TPT, advocates in Malawi and other countries at the same time fought for the affordability of rifapentine-based TPT regimens, playing a pivotal role in reducing the commodity price from $75 to around $10 per treatment course. The price should come down even further as countries increase the target populations eligible for TPT and guidelines adopt simpler screening algorithms, which will ensure that contacts of people with active TB are also protected from TB. “The price of the short-course TPT regimens has affected scaling up 3HP to all eligible recipients, as well as affected the policy and treatment guidelines whereby Malawi guidelines indicate that only those [PLHIV] newly initiated on ART be the ones prioritized for 3HP. It is unfortunate that household contacts and children under 5 years of age are still given IPT,” lamented Edna Tembo, director of COWLHA.

Is the End in Sight?

We have much to celebrate. But the fact remains that while high-burden countries have come some ways forward with TB prevention, we still have a long way to go to eliminate TB by 2030. Following the second United Nations General Assembly High-Level Meeting on TB in September 2023, we need more ambitious, time-bound targets for revising TB prevention guidelines to meet evolving global standards set by WHO and more ambitious and far-reaching implementation. And we need to firmly center TB prevention within agendas for pandemic prevention preparedness and response (PPR) and universal health coverage (UHC).

Next, we need to ensure that TPT is not lost at the national level during program implementation, especially for household contacts and other close contacts of people with TB. With a renewed focus on TB prevention under the UHC agenda, advocates can work to make these short-course treatments more acceptable and accessible to patients and to sustainably integrate and monitor community TPT programs. The importance of eliminating TB aligns with the recognized “prevention is the cure” approach prioritized by both the UHC and PPPR agendas.

Access to novel TPT treatments will remain key moving forward, even with new TB vaccines on the horizon. Countries should commit to bold, time-bound, concrete, and comprehensive targets. Here are some of the commitments we would like to see:

- Update national TPT guidelines within six month of WHO making changes to global

- Track the number of people who both start and complete TPT to obtain a measure of the quality of TPT

- Transition from IPT to newer regimens like 3HP and 1HP, for example by ensuring that three-quarters of people receiving TPT over the next five years receive a shorter regimen based on rifapentine.

- Entrench community-led monitoring in all programs to track performance, stockouts, and quality of care while supporting communities who may face challenges during their TPT treatment from initiation through

This remains the vision: neither to reduce nor control the TB epidemic but to eliminate TB by 2030, the deadline set by the Sustainable Development Goals.

Endnotes

- World Health Global TB report 2022. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis- programme/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2022

- Ryckman T, Weiser J, Gombe M, Turner K, et al. Impact and cost-effectiveness of short-course tuberculosis preventive treatment for household contacts and people with HIV in 29 high-incidence countries: a modelling analysis. Lancet Global 2023;11(8):E1205–E1216. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00251-6.

- The history of IPT is told in detail in McMillen C. Discovering tuberculosis. New Haven: Yale University Press. 2015.

- Pathmanathan I, Ahmedov S, Pevzner E, Anyalechi G, Modi S, Kirking H, Cavanaugh JS. TB preventive therapy for people living with HIV: key considerations for scale-up in resource-limited settings. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2018 Jun 1;22(6):596–605. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.17.0758. PMID: 29862942; PMCID: PMC5989571.